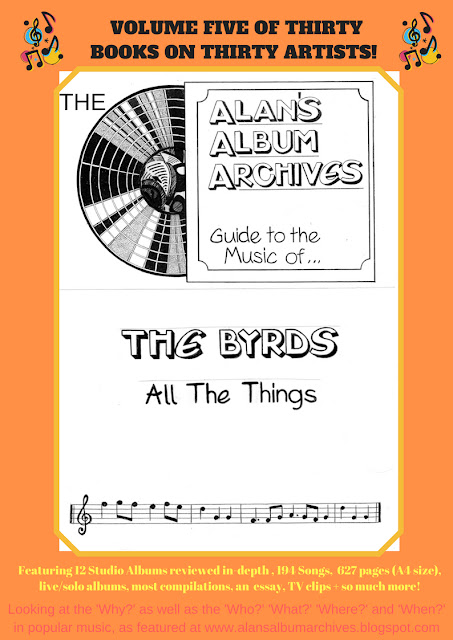

You can buy 'All The Things - The Alan's Album Archives Guide To The Byrds' by clicking here!

This Wheel’s On Fire/Old Blue/Your Gentle Way Of Loving Me/Child Of The Universe/Nashville West/Drug Store Truck Driving Man/King Apathy III/Candy/Bad Night At The Whiskey/Medley: My Back Pages/BJ Blues/Baby What Do You Want Me To Do?

The Byrds “Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde” (1969)

If your memory serves you well, then you'll recall

that being a Byrds fan in 1969 was one of the most confusing things on Earth.

In 1967 they went from being a folk quintet to a rock quartet, in 1968 they

shrunk to a psychedelic duo and by the time the hard-core country album

‘Sweethearts Of The Rodeo’ came out later that year the once high-flying band

were reduced to rubble. Losing one band member in a matter of just four years

sounds like carelessness, losing six in that time sounds like all-out war! Many

people - including Roger McGuinn himself years later - thought that the 'real'

Byrds were dead and that this replacement was just an 'ersatz' band, with a

fifth of the appeal of the old one and woeful filler. While it's true that the

Byrds mark two (well, mark five technically, what with Gene Clark rejoining the

band for all of six weeks, but you get the picture - this is the first time the

founding members are down to just one) step away slightly from the first wave

of the frontier and - unstable to the last - never quite race back up to where

they used to be, there's so much more to them than fans and critics ever gave

the group credit for. This poor unloved album, for instance, used to be a joke

amongst fans with switches of genre so wild it made 'Notorious Byrd Brothers'

feel samey and yet unlike that album there's no cohesion between anything:

traditional songs about dead dogs sit next to urgent heavy metal Dylan covers

that give way to country instrumentals, plus two superb McGuinn rockers - this

album is a real mess that doesn't know whether it's coming or going. However

music and the Byrds catalogue would have been much poorer without albums like

this one in it - full of songs that are witty and warm and wonderful and wise,

just not all of them. The biggest change between Byrds mark one and mark two is

consistency - while the original line-up never really had it either ('5D' veers

so often between genius and heinous it gives me a headache!) these records are

set to become even bigger rollercoaster rides from now on.

Fans buying this album really wouldn't have known

what they were buying: a folk-rock LP? A spyechedelic LP? A country LP? (just

look at how the band finished their stage set the stage set in this period: the

traditional ‘Buckeroo’ nestling next to a psychedelic freak-out version of ‘8

Miles High’ with the folky ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ as an encore). Unsure himself

what he wanted The Byrds to be anymore ior what they ought to be next, McGuinn

simply plumped for all of the above, thrown together in a big melting pot,

linked by nothing more than Roger's vocals and the bit of vinyl these ten songs

happen to share (I'm too fond of my copy to break it, but I bet if you did it

would splinter into ten equal pieces!) Against all odds the new-look Brds do

find their own sound, of a sort – traditional bluegrass, folk and country

played with heavy edges and a large helping of ballads, something that really

works wonders on their ninth album ‘Untitled’ (see review no 38) but hasn't

been stewed at the right temperature yet. But it's a more timid, uncertain

sound - as befits a band who were cobbled together from country and orkc

leanings and who McGuinn admits didn't really hang together. However while this

album and the ones that follow can't necessarly mix with the 'big boys' they

often have a charm and intimacy even the Byrds' big albums don't have (McGuinn

also said he kept the band together 'as I might a family business' because he

didn't want to see the name go unused - that's excactly what this album is, a

tiny shop that tries to stock everything and whole it can't compete with the

big multi-national corporations and is forever struggling to make a profit, for

customers it's so much more interesting and personal than a faceless branch

despite or even because of human error and the odd mistake).

Yes, even though 'Dr Byrds' is every bit as

schizophrenic as the title implies and even though the country leanings are

more or less guaranteed to put off the band’s rock fans and their rock leanings

put off their country fans there’s something greatly compelling about ‘Dr Byrds

and Mr Hyde’. This is probably all retrospective but ‘Dr Byrds’ does more than

perhaps any other album to pave the way for a ‘new’ sound in 1969, that troubled

year when psychedelia had ended and the back-to-roots rock/country feel of 1968

had passed. For what other album would be as daring as to put the out-thereness

of King Apathy III and Child Of The Universe on the same album as the

traditional country jig ‘Nashville West’ or the so-backwards-it-hurts country

song ‘Drug Store Truck Driving Man’? Many AAA albums will be doing this in the

70s as more and more groups realise that they can widen their scope and appeal

to take in practically everything, as long as it’s all locked together with

something vaguely similar to their traditional sound (just listen to The Beach

Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up’ from 1971 where all the band members go in very different

directions or Pink Floyd’s ‘Meddle’ which drops all-out psychedelia for heavy

rock and folk). The only other album from 1969 close to what this record’s

doing is, ironically enough, the first Crosby, Stills and Nash album featuring

McGuinn’s old sparring partner David Crosby, another album featuring three

completely different songwriters with three very different ideas of how to

write (even if the production values help link the songs together). 'Dr Byrds'

is clearly is the weaker of the two, lacking that record's originality and

drive (something that wasn't lost on McGuinn, shocked at his colleagues' sudeen

rise to fame) but then it was always going to be: CSN did everything in their

powers not to get together because they so hated their previous experiences as

band members and did so safely in the knowledge that it couldn't last forever

but because it sounded so 'right' they couldn't do anything else; 'Dr Byrds' is

more a hobby for McGuinn than anything else, a chance to tour the world as part

of a larger firm he justly felt proud of while he thought about what to do next.

While 'CSN' gets the period of unrest, love and

unfulfilled longing spot-on, in 1969 'Dr Byrds'

In 1969 this record must have sounded weird and completely unlike

anything heard before. In truth, here in 2010, it still sounds weird because

the most obvious links to the band’s old sound(s) – Rickenbacker guitar, classy

harmonies, lots of original material and an energy second to none – are

missing. Roger McGuinn, aware of how odd this new band will sound to old fans,

gamely tackles all of the lead vocals himself, the only time he ever will on a

Byrds LP . But that just makes this album sound all the stranger: Roger McGuinn

never dominated a single Byrds LP before this one which in turn features Gene

Clark, David Crosby, Chris Hillman and Gram Parsons in the spotlight (after

this The Byrds are very much a ‘democracy’ with roughly equal writing and

singing duties, if not in monetary terms!; the fact that Roger sings all ten

songs so differently to one another doesn't help matters much either) And

although McGuinn sounds terrific on his

own compositions, Roger was only really successful at interpreting songs by his

beloved Bob Dylan - as we've seen on 'Sweethearts Of The Rode' he was hopeless

pretending to be a country singer and doesn't sound all that convincing on Byrd

folk, soul and rock covers either (thankfully on future albums the other Byrds

make a much better job on their written/discovered material). In retrospect

it’s odd that McGuinn chose to record any country material at all, given how

much grief it had cost him over the past year (the ‘Sweethearts’ album wasn’t

his idea after all – it was a plan launched by new member Hillman and Gram

Parsons which was only meant to mark time while McGuinn worked on his

‘electronic’ project, sadly cancelled when the Byrds fell apart). However if

'Dr Byrds' has a dominant sound (it really doesn't, by the way) this would be

it: Clarence's country guitar riffs get more space on this album than Roger's

gleaming Rickenbacker!

The only reason this confusing album has any unity

at all is the strength of the players. Clarence White is a gem on this record

where with so much space that needs filling (this is an album notably light on

overdubbing) his playing can be heard better than anywhere else. A country

musician, he’d worked as a session musician on various Byrds records (notably

the country playing on the Byrds’ best-ever song ‘Change Is Now’) and was an

obvious choice for the band, McGuinn pleased to hear that while he was always a

country boy at heart White was such an excellent guitarist he sounded

convincing in any style, including the rock and psychedelic twinges he was

called on to play (even if he always felt more at home on the country songs).

Drummer Gene Parsons had a similar country-fied background but strangely sounds

more at home on the rockers or- where he normally excels – on the ballads. Alas he won’t get to

sing until the next album ‘The Ballad Of Easy Rider’, even on backing vocals,

which is ridiculous when you consider how much stronger his voice is than

McGuinn’s (and I say that as a fan). A natural guitarist and harmonica player,

he always sounded slightly uncomfortable on the drums, although on this album

where he’s surrounded by two such grounded guitarists his sometimes eccentric

drumming does shine through quite nicely, more so than on the Skip Battin trio

of albums anyway (great buddies that they were, their playing does tend to show

up the weaknesses of the other). Bassist John York, meanwhile, is in many ways

the long-lost missing Byrd. Fired by the band after barely a year in the job

fans have often overlooked how much York had to offer for this band: much of

the piano playing on this album and ‘Easy Rider’ are his and he contributes

many of the band’s best songs of the period, both his own and his discoveries

(‘Candy’ and ‘Fido’, plus unreleased takes on ‘Tulsa Country Blue’ and the

Pentangle song ‘Way Behind The Sun’). York never quite fit in, being that much

younger and that most subtle of leaders McGuinn probably feared having his

authority undermined in the way of another Crosby of Gram Parsons. Still, York

deserved better and makes a promising debut as a bassist, co-writer and singer

in circumstances that must have been overwhelming for him (a huge Byrds fan

with a capital everything, he couldn't believe he was a part of the band; being

country purists Clarence and Gene were to some extent snooty about the band's

past and more concerned with it's future; it says a lot for just how unsettled

Roger was after the Gram Parsons debacle that he tended to side with them, not

his adoring junior partner; you can imagine how flattered David Crosby would

have been in his place!)

We've already kind of covered whether this album has

a theme. In fact not only does it not have a theme, most ofthese songs seem to

be pulling in different directions. One thing that's worth stressing across

this whole LP, however, is how good the albu's lyrics are. On our site we

printed this review (and all the others) with a bunch of lyrics from the album

to get the 'mood' (we haven't re-printed them because of copyright issues but

I'm still glad I took the time to every week because that more than anything

helps get the 'feel' of a record before writing about it). What struck me most

about writing this lot out was how similar most of them seemed to stream-of-consciousness

psychedelia, a genre the band barely tackled (and then only when Crosby was

allowed to have a go). The country settings rather hide it but all of these

songs sound like poetry: Bob Dylan, naturally, always headed down this route

('This Wheel's On Fire' features one of his better lyrics appropriate for this

album: 'After every ladder faled there was nothing more to tell'), but his

pupil Roger has finally got the knack of copying that style after years as a more

straightforward folk or rock kind of a guy. Just listen to ‘Child Of the

Universe’ where the Byrds’ most esoteric lyric of all (ostensibly about an

alien female figure floating to the Earth, with lots of confusion as to whether

we are imagination in her reality or she in ours) is delivered like a nursery

rhyme, complete with drums accenting the 4/4 rhythms with what sound like canon

shots and one of the simplest melodies the Byrds ever came up with ('Love for

anyone who needs her, in her senses all that feeds her rolling through the

mist, floating in a sea of madness, reaching for the heights of gladness, or

does she exist?') Or the urgent politicism of 'King Apathy III' that says so

much about fashion in a Dylanesque manner, complete with the 'warning' that

hangs in the air (Middle class suburban children wearing costumes that reveal,

blindly follow recent pipers with their mystical appeal – for now...') Or how about Roger and

John's collaboration 'Candy'? ('Wind in his face, love it in lace hurling

cobwebs into time and space, meet someone who needs you now, can you throw your

love away like Candy?)' While

the rest of the band aren't approaching this album from the same angle (Gene

and Clarence only get one song on the album - their instrumental collaboration

named after their old band, 'Nashville West') even Gene Parsons'

ex-bandmates are in osn the act with 'Your Gentle Ways Of Loving Me's

delightful opening couplet: 'It's the humming of the engines of the greyhound

bus and train that keeps your memory on my mind and here with me' (as Van Dyke

Parks would say: that's a sentence!) I have a theory (as usual!): While writing

this album was McGuinn planning it as a 'return' to the 'last proper' Byrds'

album, the deeply psychedelic 'Notorious Byrd Brothers'? Did the plan change

only when he successfully wooed a reluctant Clarence to come on board? Is that

why Roger sounds so uncomfortable at times across this album?

And is that why

this record is such an odd listening experience - because it's a freak out

album dressed up not in paisley shirts and tie-dye but woolly country cardigans

and old sweaters?!?

So what we have here is a new band, wary of one

another and – with the exception of White and Parsons who were old friends –

completely unknown to each other. No wonder this album sounds at times so

sloppy; this is a band made up of members that would never normally have

crossed paths (Clarence only did because of a bit of session work subsidising

the Nashville West band). This line-up

of the band are different ages, come from different backgrounds and have

experienced very different levels of success - it's amazing that they talked to

each other (some reports claim that they didn't often!) never mind made sweet

music together. In some bands that wouldn't matter - the 'founding member'

woul;d have such a big stamp of his own authority that he would over-ride

anything. But for better or worse (generally better) McGuinn isn't that kind of

a 'leader' - trying to fill that role across this entire album so isn't him and

while the continuity makes sense (breaking the new vand in gently to hardened

fans) it's something of a relief when he goes back to being one strong wheel

out of four rather than the whole car.

Given the circusmtances it's a wonder 'Dr Byrds' is

as good as it often is, with the record catching fire like few other Byrds LPs.

McGuinn’s double-pronged attack of ‘King Apathy III’ and ‘Bad Night At The

Whiskey’ is a revelation, Roger dropping his 'act' and speaking from the heart

about politics (he isn't quite as left-leaning as Crosby and this track almost

sounds like a pastiche of CSN!) and his own insecurities (the cleverly titled

'Bad Night At The Whiskey', which isn't about the bottle - although the

narrator sounds as if he's heading there - but an early gig with this new

line-up at the Byrds' old haunt The Whiskey A Go-Go, where an unrehearsed band

were booed off stage and McGuinn nearly threw in the towel then and there)..

Even supposed throwaways like ‘Your Gentle Ways Of Loving Me’ 'Candy' and

‘Child Of The Universe’ sound genuinely exciting, with a verve and attack from

performances that the songs were arguably missing as compositions. 'This

Wheel's On Fire' is one of the band's better Dylan covers though, with the

bared teeth that the more commercially inclined Byrds often tried to hide on

full display. In truth, though, the rest of the record is a case of 'close, but

no guitar' - the other cover versions pall and the country song about a dead

dog ('Old Blue'), the tired Dylan revival medlied with a blues cover (the

closing medley of 'My Back Pages' and 'Baby What You Want Me To Do?') plus the

awful countery original 'Drug Store Truck Driving Man' (a song that should have

left the repertoire when Gram did) and the out-of-place instrumental 'Nashville

West' don't sound like The Byrds or anywhere near the sorts of places the Byrds

should be going. Played back to back with 'Notorious' (the earlier album where

it all came together)and 'Untitled' (the later album where it came close to

coming back together) and the mistakes seem obvious: this is a band who doesn't

know who it is yet or where it's going, not so much a 'Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde' as

a 'Dr Who and Mr In Hiding'. To dismiss this album from the band's catalogue

would be to lose out on some very special moments however - even whilst

committing a colossal error (as on the closing pointless rushed medley -

astonishingly it's a remake with an outtake doing the rounds that's even

worse!) this album does so with a smile on it's face and it's hybrid heart very

much in the right place.

The

Songs:

That same Dylan song [109] ‘This Wheel’s On Fire’ opens the album and

heard today seems like such an obvious Dylan choice you wonder how McGuinn got

away with selecting it, seeing as The Byrds always tried to select the more

unusual Bob songs of the 1960s. But in actual fact ‘Fire’ was still an

unreleased song in early 1969, simply one track among a number of songs from

Dylan’s ‘Basement Tapes’ given to McGuinn to select from and Brian Auger and

Julie Driscoll had yet to record the song, never mind enjoy a #1 hit with it.

That might explain why The Byrds take more liberties with this song than

perhaps any of the other zillions of covers of it: the opening chilling fuzz

box drawl and the deliberate slowing-down of the melody make it sound almost

unrecognisable as the tune we know and love (so that the chorus, far from being

the punchy hook in the middle of the song, is more like a gradual unfolding of

the verses). Full marks to Clarence White for the fiery guitar solo, which at

once manages to sound like McGuinn’s traditional sound and gives the Byrds a

much harder edge than we’re used to hearing from them (even if, ironically, the

country guitarist hated his ‘out-of-tune’ work on this work and wanted to get

it substituted with the rather less-together outtake heard as a bonus track on

the ‘Dr Byrds’ CD). The slowing down of the song also drags the time out to a

(for the Byrds) ridiculously long 4:44), helped partly by some experimental fun

from McGuinn with his new synthesiser, mimicking feedback before the sound is

gradually shut off. The result is quite a powerful reading which, together with

McGuinn’s nervy and sometimes off-key lead, is one of the band’s more

believable and involved Dylan covers. You have to worry for fans coming to this

album on the back of ‘Sweethearts of the Rodeo’ though – different style,

different genre, different feel, different everything!

[110] ‘Old Blue’ switches the band straight back into their country

setting, but even though this is obviously a song inspired by the traditional

country stalwart the dead dog the effect sounds more like a rock-country hybrid

than the tracks on the last album. Even though McGuinn’s narrator is waving a

fond farewell to his old faithful hound ‘Old Blue’ after many years of faithful

service, this is no elongated lament but the snappiest and most upbeat song on

the album, played with a fun and zest quite unlike the last track. McGuinn

turns in one of his better vocals too, suggesting that this song was his choice

(he gets the credit for arranging this traditional tune, but that doesn’t mean

anything in The Byrds’ canon where songwriting credits were forever in

dispute!) and unlike many songs on this most skewered of albums it really suits

his country-rock hybrid band. Listen out too for the hand-claps which really

make the song, emphasising the off-beats of this song’s tricky compound time

structure. The result is one of the band’s better performances of the album,

all the more impressive given that – along with ‘King Apathy III’ – it was

taped during the first session for the album. The Byrds seemed to have some

fondness for canines with this line-up too: see ‘Fido’ on the next album (were

they Byrd-dogs perhaps?!)

[111] ‘Your Gentle Ways Of Loving Me’ is one of the unexpected

highlights of the album, even if McGuinn sounds deeply uncomfortable singing

such a subtle country song which was a regular staple of Nashville West, the

pre-Byrds band featuring White and Parsons. A sweet, swaying rhythmic song,

well suited to the band’s new rock-country hybrid sound, this song sweeps along

nicely and shows off the band’s interplaying skills like few others in this

period (if only the backing track of this song had been included on the CD as a

bonus, as the Sony re-masters of the late1990s so often did). The song is also

quite subtle – you may not pick up from the lyrics at first that this song is

sung in the past tense, with the narrator looking at the greyhound bus he knows

still travels to where his sweetheart used to live and sighing over lost

opportunities. Gene Parsons’ harmonica playing is the highlight of the song, as

it will be on many Byrds tracks and really adds to the wistful feeling of this

under-rated song.

[112] ‘Child Of The Universe’ is another under-rated track that sounds

quite unlike anything else I’ve heard. As discussed, on the one hand it’s a

simple, almost nursery rhyme song with its bad a-daa bad a-daa bad a-daaaaah

verse and it’s rattled canon-fire drums which act to emphasise one of the

simplest backing tracks The Byrds ever made. On the other, it’s an absolute

‘sea of madness’ to quote the lyrics: the Goddess of the song might or might

not exist; the ‘work that she begun’ may be the Earth in the past, present or

future or not our planet at all; the ‘child of the universe’ may be the playful

creator behind our existence or may be the aged God we’re used to hearing about

getting younger the further she goes forward in time (I was so much older then,

I’m younger than that now); the whole song might be about the ultimate question

of life – or it might be pure gobbledegook. Fans are used to hearing this sort

of thing from bands like The Moody Blues and Pink Floyd where questioning the

nature of the universe is their complete reason d’être. Hearing this sort of

philosophy from the Byrds sounds downright peculiar – with the possible

exception of the Bible extract ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ and the odd David Crosby

epic (CSNY will re-use the phrase ‘Sea Of Madness’ from this song in 1970),

nothing else from the band’s back pages ever sounded remotely like this. We’ve

often said in our other Byrds reviews that it’s a shame McGuinn didn’t explore

his philosophical side more, given how the life-questioning elements of his

lyrics often urge him to come up with his best songs. This is McGuinn’s most

extreme example of writing a song around an idea and adding the music later,

perhaps going a bit too far in compacting the song to something simple enough

for people to sing along too. The band do a sterling job with such complex

material with some nice harmonies from York and Parsons, even if the playing is

a little too heavy handed for what is already quite a thematically ‘heavy’

song. The song was written first for the equally odd film ‘Candy’, starring

Ringo Starr as a randy Mexican gardener (believe it or not one of the more

‘normal’ features of the film!) but despite what many Byrds commentators have

written down the years doesn’t seem to have much of a link that I can see –

even if Candy herself is as confusing as the Goddess in this song, she’s hardly

the creator of the universe, just an instigator for the madness that goes on

around her. Whatever the inspiration, though, ‘Child Of The Universe’ is one of

The Byrds’ greatest ever songs I think, really stretching the songwriting format

to its limit and the impenetrable way it discusses such ‘big’ concepts as the

creation and purpose of man really suits this half-simple, half woefully

complicated song. It’s absence from both Byrds box-sets is nothing short of

criminal.

[113] ‘Nashville West’ is about as extreme in opposites as you can

get. A rollicking country-rock instrumental which wouldn’t have sounded out of

place on an album by a more traditional outfit, this song was the ‘calling

card’ for White and Parson’s previous band. Hearing the title song of another

group played by The Byrds sounds slightly weird, not least because it’s the

last time we get to hear White and Parsons playing so fully in the country

idiom during their run with the band, but McGuinn’s Rickenbacker acoustic playing

does at least fit in well with the style, adding a more modern 1960s sound to

proceedings. Recycling this track though suggests either that half the band

still wanted to be in Nashville West but The Byrds paid better or that the

whole group were so short of material in this period that they reached

backwards to everything they could get. Just as the Byrds seem to be getting

too country-fied, however, in comes that crashing ending with a scream from one

of the band and Gene Parsons’ garbled nonsense commentary, adding a rock kick

at the end typical of this band. Overall, it’s great to hear classy musicians

like McGuinn and Clarence White playing unimpeded (and York’s bass playing is

every bit as melodic and inventive as his replacement Skip Battin’s), but

unless you’re one of the few fans coming to the Byrds out of a love of

traditional country you probably won’t want to hear this song too many times.

[105b] ‘Drug Store Truck Driving Man’ is well loved by many a Byrds fan

and is probably the most famous recording on the album. But for me this

so-called comedy song is awful, a recycling of the not-very-good-anyway ‘So You

Want To Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’ in the way it nastily damns the whole of the

country scene (just like it’s predecessor slammed rock music) and an unwelcome

leftover from the Byrds’ worst album ‘Sweethearts Of the Rodeo’. The song,

written by McGuinn with Gram Parsons – the only song these two natural enemies

ever wrote together – lampoons country disc jockey Ralph Emery who,

understandably, had his doubts about why a successful rock group should ever

want to ingratiate themselves with traditional country stars. The Byrds, in

turn, question in this song why such a supposedly country-loving

music-promoting man needs to spruce up his show with commercials for truck

parts (for which Emery reportedly got a commission). The band were quite

genuinely aggrieved by Emery’s comments, especially Gram who was about as

traditional a country performer as you can get, but their reply to Emery’s

challenge to their credentials arguably proves his point. This song is one of

the most boring of the band’s career, simply repeating the one-line melody with

minor variations throughout the song (it doesn’t even have a chorus, just

repeated words to the same melody) and the playing is woefully inadequate

without the band’s ‘true’ country member Gram Parsons there to show them how to

do it. Roger McGuinn has an awful lot of skill and his voice is one of the most

under-rated in rock, but he’s a straightforward kind of singer, unable to offer

the right shades of contempt and sarcasm this song requires, making you wonder

if McGuinn genuinely knows that this song is meant to be tongue-in-cheek. One

of the most uncomfortable Byrds songs to sit through, ‘Drug Store Truck Driving

Man’ misses the point so many times over you wonder why more country stars

didn’t come out and slam the band. Very sloppy work.

[114] ‘King Apathy III’ is much better, one of the brightest spots on

the album with McGuinn this time channelling his anger in a more sensible and

sensitive cause. Despite the fact that they end up creating two of the most

politically charged bands ever made (Crosby, Stills and Nash and the Flying

Burrito Brothers) The Byrds themselves were characteristically cool about getting

involved with political matters. The closest they ever got was this song where

McGuinn slams the multitudes for not caring about the communinities around them

and the inability of politicians to inspire their citizens to get behind them.

Just as the song is getting a bit too vague in it’s target and what it means to

the narrator, McGuinn adds a classic middle eight, dropping the fiery rock

backing in favour of some country picking, setting out the philosophy of this

schizophrenic album with the lines ‘so I’m leaving for the country to try and

rest my head’ (even if it does sound like a steal from Mike Nesmith’s ‘Naked

Permisson’ from the Monkees’ 1968 TVF Special ’33 and 1/3rd

Revolutions Per Monkee, which is every bit as schizophrenic, even dividing the guitarist

in two as he sings it!) Neither country nor rock on their own are offering the

pioneering traditionalists The Byrds the space they need any more so McGuinn’s

chosen both. The only downside of this classic song is that the band, playing

in their first studio session together, clearly don’t understand the song yet

and turn in a very tentative performance here. ‘King Apathy III’ will sound a

million miles better in live concerts later on in the year, where the lurch

from rock to country really is ear-catching rather than a nice idea that

doesn’t quite come off and McGuinn stops showing off his skill on the guitar

and starts playing from the heart. Still, even with the rougher edges intact,

this is an impressive song with some great images in the lyrics: ‘freaks

collecting stain-glassed rubies, pulling gently on the strings’ ‘middle class

suburban children wearing clothes that reveal’ and ‘all the changes

superficial, apathy still the king, liberal reactionaries never doing anything’

are all spot-on observations of life in the late 1960s when so many of the

youth movement wanted to change the world – and got waylaid by the realities of

politicians pulling the strings.

You’d expect [115] ‘Candy’ to be another track from the ‘Candy’ film

wouldn’t you, especially as the song fits the plot line so much better? But no,

this McGuinn-York collaboration got dropped at the last minute (reportedly

because York was an unknown writer with no previous songwriting credits to his

name) and it’s the film’s loss as far as I can see. Another song that segues

breathlessly from country picking verses to rock and roll-come-psychedelia

choruses, ‘Candy’ finds The Byrds at their stretched-out best, especially the

elongated middle section that finds both McGuinn and White on fine form (and

which was – shockingly – cut from the record; if you ever get the chance do buy

the CD version of this album which apart from some great sleevenotes restores

the middle section of this song, uncredited, to it’s proper place). The factor

that made ‘The Notorious Byrd Brothers’ such an enjoyable album wasn’t so much

the compact two-minute songwriting as the way the band would break their own

formula when the song called for it. ‘Candy’, in its originally intended longer

edit, sounds like the long lost twin of ‘Change Is Now’, with two typically

condensed verses spelling out the film’s plot segued by a truly surreal and

breathtaking ride into the unknown. Another forgotten aspect of this sweet

little song is the lyrics – the half-rhymes, forced on the writers by the

shortened verse structure, are very clever (‘very profound, merry go round

spinning innocence and dreams, can you believe all you perceive? Love is never

what it seems to be’ is one of the Byrds’ best ever couplets, packing so much

into it’s two lines) while the chorus pun of ‘throwing your love away like

Candy’ (both the sweets and the girl in the film) is an uncharacteristically

funny joke from what is generally the most serious of bands. Another often

overlooked gem.

The best track on the album as a whole, however, is

probably McGuinn’s blues-rock hybrid [116] ‘Bad Night At The Whiskey’. At the heart of this

track is yet another pun – far from propping up the bar as the morose narrator

suggests, this track is a reply to a critic who damned a show the new-look and

under-rehearsed Byrds played at the Whiskey-A-Go-Go in California. In his heart

of hearts McGuinn agreed with the critic and questioned himself over his

decision to continue The Byrds after so many band members had left, although

ironically it’s this very track questioning their existence which shows off the

many skills of this line-up of the band. The blues elements are quite unlike

anything the band ever tackle again, which is a shame as Parsons’ elaborate but

suitably chugging drum parts are matched by a classic walking bass from John

York and a chilling lead from Clarence White. The whole effect is so enticing

that you really sit up and take notice when this track comes on the CD, with

the song’s anger really penetrating through the murk of this often meandering

record. If I didn’t know better I’d say that this song was a pretty nifty piece

of psychology from McGuinn on why the Byrds broke up in the first place too:

Roger was famous for his love of a quiet life and hatred of any outward show of

emotion (something made much harder by having such vitriolic musicians as

Crosby, Hillman and Gene Parsons passing through the ranks) and the line about

‘although you’re smiling your hate will not cease’ sums up just how unprepared

McGuinn was for the paranoid back-stabbing that often goes on in the best of

bands. ‘Just put yourself at ease and leave my soul in peace’ also sounds like

a genuine cry from the heart, especially the way McGuinn sings it here in

perhaps his most committed vocal of all. This song plainly meant a lot to its

author and was revived for many concerts down the years. However, it turned out

many years later that only the tune is McGuinn’s – the words were penned by

Joey Richards, a friend of McGuinn’s (both were inducted into the subud culture

where Jim McGuinn was given his new name of ‘Roger’) who also happened to be

the room-mate of Peter Tork at the time (and is credited on that band’s ‘For

Pete’s Sake’ track, used as the opening titles to the band’s second TV season).

Whether co-incidental or not, however, the song is clearly born out of

frustration at being told you’re not good enough by somebody and remains one of

the hardest, heaviest, angriest and greatest of all the Byrds recordings.

If you don’t believe how much that song meant to

McGuinn and the rest of the band, you only have to play it back to back with

the album’s closing [67b/117] Medley, a truly bizarre curio that sandwiches together a Dylan

song the band had already recorded on the ‘Younger Than Yesterday’ album, a new

blues instrumental written by the band and a closing romp through the famous

1950s Jimmy Reed song ‘Baby, What Do You Want Me To Do’, made most famous by

Elvis in his 1968 leather comeback TV special (where if you watch the complete

session tapes he songs the song at least a dozen times!) The Byrds don’t sound

at home on any of these songs – play the polished 1967 version of ‘My Back

Pages’ next to this 1969 version and its amazing how much sloppier and raw this

unpolished band are, especially in the harmony stakes. What’s weirder is that

this part of the medley only hangs around for 30 seconds, barely worth getting

the publishing credits right, before lurching into an instrumental that sounds

like at least 900 others out there, complete with gulping harmonica and fuzz

guitar. The closing ‘Baby What Do You Want Me To Do’ sounds even rawer and even

less dignified, with some especially sloppy double-tracking from McGuinn,

although the rest of the band aren’t much better – even Clarence White’s guitar

solo sounds uncharacteristically tired and subdued. The song then ends finally

with a little riff the band nicknamed ‘Hold It!’, a jokey little instrumental

the band started playing in concerts before the encores after McGuinn commented

that, having scored a #1 hit with their first single, the band had never had to

play so far down the bill they never had to play two sets and unlike

practically every other 1960s band barring the Beatles had not come up with

their own ‘we’ll see you for the next set’ riff. Sezing on this album as an

opportunity to say that the Byrds were still very much alive and with a second

‘act’ still to come, the band put their jokey riff on the end of this album –

where it’s been confusing fans ever since. Even with this hidden meaning,

however, this is a woeful excuse for a medley and one that I assumed for years

must have been a one-take wonder dashed off when the band ran short of time

(you even hear McGuinn shouting ‘quiet Clarence’ at one point) – before the CD

version of ‘Dr Byrds’ came out containing an outtake that was even worse! Not

one of the band’s better ideas...

Other Byrds reviews from this site you might be interested in reading:

A Now Complete Link Of Byrd Articles Available To Read At

Alan’s Album Archives:

'Mr Tambourine Man' (1965) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/news-views-and-music-issue-134-byrds-mr.html

'Mr Tambourine Man' (1965) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/news-views-and-music-issue-134-byrds-mr.html

‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ (1965)

http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2017/03/the-byrds-turn-turn-turn-1965.html

'(5D) Fifth Dimension' (1966) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/news-views-and-music-issue-49-byrds-5d.html

'(5D) Fifth Dimension' (1966) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/news-views-and-music-issue-49-byrds-5d.html

'Younger Than Yesterday' (1967) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2011/08/news-views-and-music-issue-108-byrds.html

'The Nototious Byrd Brothers' (1968) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/review-20-byrds-notorious-byrd-brothers.html

'Sweethearts Of The Rodeo' (1968) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2014/06/the-byrds-sweetheart-of-rodeo-1968.html

'Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde' (1969) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/news-viedws-and-music-issue-68-byrds-dr.html

‘The Ballad Of Easy Rider’ (1969) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/the-byrds-ballad-of-easy-rider-1969.html

'Untitled' (1970) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/review-38-byrds-untitled-1970.html

'Byrdmaniax' (1971) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/the-byrds-byrdmaniax-1971-album-review.html

‘Farther Along’ (1972) http://www.alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/the-byrds-farther-along-1972.html

'The Byrds' (1973) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-byrds-1973.html

Surviving TV Appearances http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-byrds-surviving-tv-appearance-1965.html

Unreleased Songs http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-unreleased-songs-1965-72.html

Non-Album Songs

(1964-1990) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-non-album-songs-1964-90.html

A Guide To Pre-Fame Byrds

Recordings http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-pre-fame-recordings-in.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part One (1964-1972) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part Two (1973-1977) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums.html

Solo/Live/Compilation Albums Part Three (1978-1991) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_9.html

Solo/Live/Compilation Albums Part Three (1978-1991) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_9.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part Four (1992-2013) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_16.html

Essay: Why This Band Were Made For Turn! Turn! Turn!ing https://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/byrds-essay-why-this-band-were-made-for.html

Essay: Why This Band Were Made For Turn! Turn! Turn!ing https://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/byrds-essay-why-this-band-were-made-for.html

great to see this album get such a detailed review.i always rather liked it and you have confirmed my own thoughts[though i've always enjoyed dstdm]you've pointed out interesting aspects of songs that have been favourites right from when i first heard the album.candy and to a lesser extent child of the universe always got slated in retospective reviews,but as well as the strong atmospheric sound you highlighted the very pointed lyrics[candy etc]-they always came out loud and clear in that accusing early dylan way,every time that i play the record. thanks, a very interesting read.

ReplyDeleteThankyou kindly! I rather like it too, I'm not sure why people dislike that album so much - it is weird, but usually in a very wonderful way! 'Child Of The Universe' is a great song! 8>)

Delete