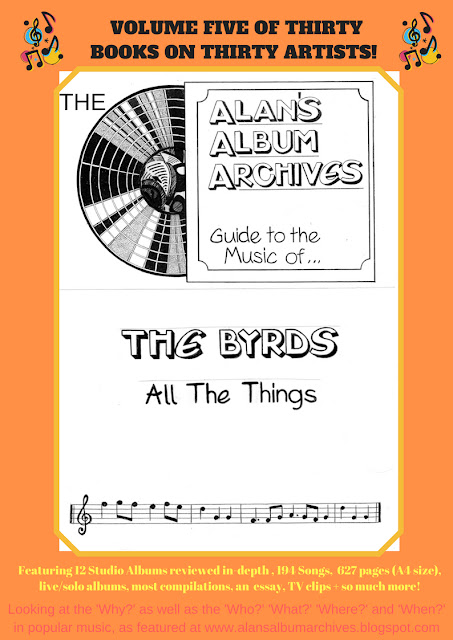

You can buy 'All The Things - The Alan's Album Archives Guide To The Music Of The Byrds' by clicking here!

The Byrds "The Notorious Byrd Brothers" (1968)

Track Listing: Artificial Energy/ Goin’ Back/ Natural Harmony/ Draft Morning/ Wasn’t Born To Follow/ Get To You// Change Is Now/ Old John Robertson/ Tribal Gathering/ Dolphin’s Smile/ Space Odyssey (UK and US

Were the Byrds ever really notorious? Liked, admired

and respected by their peers they may have been, but most people tend to think

of the Byrds as angelic choir boys rather than the in-fighting back-stabbers

they actually are if you read one of their biographies. Notorious Byrd Brothers is fittingly named, however, both for the

fact that this is the album the Byrds famously started as a quartet and finished

as a duo (they’d be down to Roger McGuinn on his own in six months’ time) and

all of the love-hate brother-like relationships going on within the band at the

time (that’s brotherly love in the sense that’s shared by the similarly

back-stabbing and in-fighting Wilsons, Davies and Gallaghers brethren on this

list!) Not content with their shoddy treatment of fragile genius Gene Clark,

whose own gloriously complex and groundbreaking songs were replaced by songs

full of snipes about their former partner’s inability to cope with the pressure

of fame, the band self-destructed completely during late 1967. Drummer Michael

Clarke walked straight after these sessions, fed up with being jeered at for

his playing which had actually come on leaps and bounds during the Byrds’ years

– and David Crosby got unceremoniously booted out of the band in the end of

1967 because his songs were, ahem, ‘not very good’ and they’d be better off

without him – the 1st CSN album is barely a year down the line at

this point, remember.

In fact, the more I read about this most delightful

of dysfunctional bands, the more confusing it seems that such different

musicians ever even crossed paths in the early 60s never mind recorded

four-and-a-bit albums with losing just the one member. Hardly any bands stay

the best of friends during their recording years but this must surely be one of

the only bands to have started seriously rowing before they even got a record

contract! The other Byrds not mentioned so far, Roger McGuinn and Chris

Hillman, were never the most prolific of writers during the 60s and sure enough

they got so desperate for material that they raided Crosby’s latest batch of

demos and early recordings for this album, altering the lyrics along the way

and causing yet more friction among the five now scattered Byrds. As a parting gesture they decided not

to put Crosby on the cover and 'replaced' him...with a horse! (to be fair this

sounds like a bit of 'horse-play', an unplanned joke that got out of hand when

the band realised they didn't have a fourth head for their planned photo-shoot

in a shack in the hills and grabbed the nearest solution, but it genuinely

riled Crosby who still considers it a spiteful comment about his role in the

band).

You see, for all my accolades about it later on in

this review, Notorious really isn’t

the properly thought-out and painstakingly crafted album the Byrds want you to

think it is at all. Notorious is

really two albums in one, partly recorded with an on-form Crosby at his

unrepeatable 68-69 peak and then partly re-recorded in the singer’s absence;

the other songs feature McGuinn and Hillman working more or less alone to plug

up the holes and complete the record on time. Even with that convoluted and

confusing background, most of this album’s highlights still belong to Croz. His

lovely harmonies shimmer throughout this record and his songs – Draft

Morning, Tribal Gathering and Dolphin’s Smile - are among the Byrds’

most atmospheric and groundbreaking tunes. In fact Crosby probably wanted to

keep these songs for himself and CSN/Y, but after telling him his new songs

were useless and weird, the rest of the band found themselves short of material

and cannibalised old recordings and what they could remember from Crosby’s

half-completed demos (that’s why all of these songs bear co-writing credits but

they’re really Crosby’s with the odd line added!) Recorded in the most miserable of

circumstances, then, with band members tugging at the reigns this way and that,

unable to agree on anything any more, The

Notorious Byrd Brothers should be a horrid, pitiable mess - the album the

Byrds started as a quartet and ended as a duo (counting the loss of Hillman and

Gram Parsons on the next record, that's five members in four records!) Given

that the band had already sounded weary and disillusioned on their last album

('So You Want To Be A Rock and Roll Star' is cynicism on a pop-sicle stick) you'd

be fully within your rights to look at the dating (1968 was the most turbulent

year for music, at least across the 1960s, full of unrest assassinations and Nixon)

and find yourself be expecting an incoherent angry, screaming rant that doesn't

hang together.

Instead Notorious,

is one of the greatest albums ever made, not least because it's one of the most

beautiful albums ever made. How on earth did a band who could barely stay in

the same room as one another and all felt as if their futures were uncertain

and hopeless find it in themselves to create such powerful, restive songs is

beyond me - but they found the knack of turning all that tension into gold just

in time. Many of the songs are gorgeous, melodic ballads that float with a

serenity and calm and even those that aren't have lyrics that are wise beyonf

their years, full of references to brotherly love and getting along (even if

through gritted teeth) - a world away from the sometimes childish inter-band

rants taking place (listen to the band argument taking place during 'Dolphin's

Smile' and smuggled unlisted onto the end of the Norotious CD re-issue for an

insight!) Crosby is in particularly blissed-out state on this record, with his

'Dolphin's Smile' and 'Draft Morning' amongst his most hauntingly gorgeous

compositions (finished off by his colleagues after kicking him out the band

when they realised they needed material in a hurry). McGuinn's 'Space Oddysey'

imagines a happier future fifty years down the line, with the seeds planted in

the 1960s ending up sprouting into gorgeous fruit just a generation or so later

(sadly, we're still waiting). Hillman's 'Tribal Gathering' (written with

Crosby's help) is the single most 'brotherly love' song The Byrds ever made,

full of the peace and harmony and optimism that wasn't there in the studio. The

joint 'Old John Roberston' remembers a strange old man the teenage Chris used

to bully for being different and which the duo now want to worship and

celebrate in their new-found love of humanity. And best of all the pair's

classy fittingly turbulent but somehow serene

and accepting 'Change Is Now' shrugs it's shoulders and accepts the now

for what it is. 'The Notorious Byrd Brothers' may have been recorded in trying

circumstances but only the opening track 'Artificial Energy' (the Byrds' only

drug song, whatever case has been made for 'Eight Miles High') sounds anything

like the angry, angtsy songs you might expect and even that's clever in a

'we'll-write-a-song-around-the-new-production-gimmicks-we've-just-found-instead-of-simply-using-them-for-no-other-reason-than-they-sound-cool

kind of a way).

Then again, if there's a theme to this record it's one

of brotherly love and how wonderful it is to be alive in 1968 when mankind is

coming together and everything in the future will be different - the last thing

you'd have expected in the circumstances. 'Tribal Gathering' is the most extreme

example, inspired by the 'Human Be In' at San Francisco's Golden Gate Park (a

kind of early version of the Monterey Pop Festival), the first time so many

young people had gathered in one place without any call for it. 'Natural

Harmony' is a close second, with blurred images of people 'walking streets side

by side, head thrown back, arms open wide' as if in a trance from love. 'Old

John Robertson' is Hillman's adult guilt over his childhood antics with an

eccentric character he now feels had much to teach him. 'Wasn't Born To

Follow', soon to be a hippie anthem thanks to it's use in the 'Easy Rider'

film, is a statement that everyone is unique and have their own lives to lead.

'Draft Morning' sees two worlds moving in parallel: one a beautiful sunlight

morning paradise as the narrator makes his escape, another a horrifying image

of battlefields, our guide now 'up early to learn to kill'. 'Change Is Now'

delights in the change the youth of the day are bringing and in typical Byrds

style tries to tell us that our future sci-fi selves will always be linked back

to our country pasts (with one of the greatest instrumental breaks in rock

music history. Seriously, if you're not convinced of the power of the hippie

dream after the end then either you've been listening to too much George W Bush

or you need a new pair of ears - let's play this album the next time

there'a war on and see how quickly both

sides put down their arms!) 'Get To You' is a story-song about an aeroplane ride that yells with delight 'that's a little better!' as if simply taking this

one journey has improved the narrator's hopes for mankind's spirits. 'Dolphin's

Smile' tells us that the amphibians have beaten us to our universal peace and

understanding anyway Finally, 'Space Odyssey' imagines a brighter future when

our petty human differences have been put aside. In a nutshell the album's

message is this: 'Change is now, all around - dance to the day when fear is

unknown'.

'Notorious' then is a real album of it's day - and

yet in many ways it's straining at the leash to go even further onto the next

adventure. For a time it was set to do exactly that. The ever mischievous Crosby wanted 'Triad' for the album, a tale about his emerging lifestyle as part of a

menage a trois that rejected all traditions of marriage and understanding with

the tagline 'I don't really see - why

can't we go on as three?' Shocking for some even today (I took great delight in selecting this track for one of my music lesson assignments to see if it still

had the power to shock - what do you know? It did!) , 'Triad' is the logical

conclusion to this album's boundary pushing but went too far for McGuinn and

Hillman who threw the track out along with the singer (Crosby hated the drippy

'Goin' Back' and only helped to record it on the understanding this song would

be left alone - in that context I'm with Crosby, straining towards the future

rather than woefully looking back to the past, although it's too far ahead of

our times now - it would have caused a revolution in 1968, which was exactly

what the guitarist wanted! He gave it to Jefferson Airplane to record instead,

where it made even more sense sung by Grace Slick's feminine voice but got far

less attention). While an understandable absentee, I still say it's this

album's loss - the mischevious debate held at this album's generational rallying

call that would have allowed the album to go even further than reflecting it's

times and imagining a brighter future - it could have lead them as well.

Now that we have the album re-issued on CD (with

lots of brand spanking new bonus tracks) the most revealing moment comes not

from the album itself but the unlisted 'hidden track' squirrelled away at the

end - perhaps the most revealing ten minutes of any Byrds CD. The Byrds are

trying to record 'Dolphin's Smile', the most serene and beautiful moment from a

record full of them. Those harmonies float. Roger's guitar sounds like an ocean

wave. The song takes shape. It's beautiful. And then - *crash*. Michael Clarke

is throwing all his weight behind his drums like he's Keith Moon. Crosby urges

his pal to 'try something gentle'. Clarke refuses. 'It's not beyond you

Michael!' Crosby retorts before adding that he's always like that when someone

suggests something he doesn't like. Producer Gary Usher kindly intervenes,

telling him he usually has some good ideas. Clarke gets sulky. Then he gets

cross, telling Crosby he's a 'drag' and 'attacks me all the time'. The band

lose their cool, Crosby barking the unhelpful suggestion 'try playing right!' 'Can't

you play the drums?' quits Hillman.'Send me away then!' cries Clarke. 'Poor

Baby!' cries Crosby. 'Well, I never liked the song anyway' digs Clarke, aiming

his digs where he knows they'll hurt. A band argument intervenes, the response

of the others sounding as if that was the third one they've had just that day. Within

mere months from this session (weeks in Crosby's case) both men are out the

band. The ironic thing is the final version of 'Dolphin's Smile' - cut mere

hours later - is beautiful. Clarke not only nails the lick the others are

trying to get him to play here, he's invented a whole new one that's much

trickier and complex than anything Crosby was trying to get him to do. Clarke's

greatest drumming is on this album, in fact, especially his hard pulse and relentless

rat-ta-tat that turns 'Draft Morning' drom a drifty dreaming song about

rebirth into a song about escaping the draft. Once again, the magic of

'Notorious' is how it took the sheer chaos of events like these and turned them

into positives, using band arguments as the springboard for pushing the

boundaries of what it even means to be in that band.

While fans have always debated which Byrds album is

the best (unlike The Beach Boys who always get lumbered with 'Pet Sounds' or

Simon and Garfunkel with 'Bridge Over TRoubled Water', there's never been a

general consensus on which Byrds record is 'the one') and I have soft spots for

many, I have to go with 'Notorious'. No other Byrds album sounds this

'complete'. All Byrds albums have some master stroke on them somewhere (yep,

even 'Byrdmaniax'!), but 'Notorious' is a remarkably consistent album where

practically every song is a gem (only a rather dreary cover of 'Goin' Back' lets

the field down). Gary Usher (once Brian Wilson's writing partner) glorious production

is the band's best: it fills up the sound with all sorts of squiggly

synthesiery bits (back when synthesisers were worth hearing and didn't sound

the same on every bleeding record as they will in 210 years' time) and yet the

vocals, guitar, bass and drums are always upfront and centre in the band's

sound (not always the case down the years!) Perhaps best of all there are three

terrific songwriters all arguably hitting their peak (or certainly one of them)

all at the same time: while Gene Clark was the Byrd who ruled the roost on

albums one and two, with McGuinn on album three and Crosby and Hillman swapping

works of genius on album number four it's 'The Notorious Byrd Brothers' where

each man's distinctive style really comes into it's own. The songwriting

partnership struck up between Roger and Chris is especially good - light years

ahead from the tired 'Rock and Roll Star' - and makes you wish they'd started

writing together earlier: Hillman's love of roots and McGuinn's love of the

future makes for a terrific blend of styles that, for now, are truly compatible

(alas this record, only the second time the pair work together, is also the

last and Hillman is gone after just one more LP). Above all 'Notorious' flies

higher than any other Byrds album because it's the one that's more than the sum

of it's parts: the sequencing of songs is genius, with tracks seguing into each

other most naturally (despite coming from so many different sessions with so

many different line-ups playing on them) or linked by sound effects that

somehow work; each sounding as if it's 'meant to be'.

Best of all, each song takes you on a journey somewhere new - with most of the

journeys somewhere the Byrds have never been before. Even more than most groups

around in the ever-changing sixties, the Byrds seemed to change their style as

often as they changed their socks in this period, possibly more. Between 1966

and early 68 they went from Dylan-loving folk-rock cover artists, to Ivy League

type pop merchants to space age cowboys and psychedelic spaced-out atmospheric

splendour in the blink of an eye. We're used to hopping somewhere new with each

Byrds flight - that's something fans just have to do to keepn up (although the

sea-change from Notorious to the next record is a leasp to far for most,

however well it's regarded nowadays). If

you think that change in style in a little under three years is weird, however,

wait till you play this album, with its three-minute compact symphonies where

two or three of these styles are quite naturally welded together, with

traditional rockers breaking off for a good old country steel guitar solo in

between bursts of feedback, not to mention setting a space-age message from

infinity and beyond to a 19th century sea shanty backing. The

curious thing in retrospect, though, is what's happened to the 'country'

influence - first heard on the second album's 'Satisfied Mind', it's been

picked up by mandolin player Hillman for his sogs on 'Younger Than Yesterday'

but now - nothing (well nearly nothing, there's a little bit on 'Old John

Robertson' but that's still more rock than country and a brief pedal-steel

yee-hah kick to 'Change Is Now' which lasts for all of eight seconds per verse;

the session tapes revealed a lot of country songs were tried bu never used,

including Hillman's first go at future Manassas song 'Bound To Fall'). The

Byrds are about to take the biggest leap into the unknown of their career and

yet seem on this record to have turned their backs on the sound they're about

to go mainstream with (suggesting that Gram Parsons played an even bigger role

in the next record than suspected!)

What's odd, too, is that a 'country' record is

exactly what you'd expect from the date, the album title (much more likely for

a country band than a rock one) and the album cover: three Byrds and a horse in

a shack in the woods (left to right: Hillman, McGuinn, Clarke, Horse - the band

changed facial hair styles so often it's hard to keep track). Late 1967 and

early 1968 was all about being as 'weird' as possible - yet here are The Byrds,

just weeks on from The Beatles' weird album sleeve for 'Magical Mystery Tour'

in animal masks and The Stones' wizard-centric 'Satanic Majesties' - shooting

what seems like the lowest budget and plainest cover imaginable.Where are the

tribal gatherings? the dolphins smiling? The space oddyseys? Instead we get a

shack in the forest with a tin roof so badly someone really needs to call in

the builders...

That's about the only thing that is down-to-earth

about this record though: 'Notorious Byrd Brothers' is a real 'trip' of a

record (not withstanding the deeply anti-drugs and out-of-it's-times song with

which the record begins), one that comes in lurid psychedelic colours and which

sounds as if - at last - a lot of time has been spent on getting everything

just right. The bad news is that The Byrds never achieved this again before or

since - just think what Gene Clark or even Gene Parsons might have done with

this much care and attention lavished on their songs and weep. The good news is

that against all the odds The Byrds got near perfection at all during the

making of one of the most turbulent, frustrated, angry, back-stabbing sessions

ever held for a record. This album isn't just notorious, it's noteworthy, one

of the brightest shining gems from a golden age in music that deserves every

accolade going.

The

Songs:

The lovingly lethargic [73] Artficial Energy is an interesting place to start, with the

band singing of ‘coming down’ off something, but whether its drugs or a musical

elation we never find out. The song even manages a cheeky reference to

another alleged drug song with the line ‘took my ticket to ri-i-i-de’ – again

giving us mixed messages of music or drugs. Each of this song’s parts should be

energy personified – Chris Hillman’s bass stretches its legs every chorus, the

horns blast at double-time and the song’s tempo is definitely upbeat. McGuinn -

the least drugged up member of a drugged up band - delivers a lead vocal

gloriously blurred and out-of-it, suggesting either that he's made a rare

exception during the making of this record or that he's been closely watching

how his colleagues act while 'tripping'. However what's odd for the times is

how un-1967/68 these lyrics are: the drugs/music doesn't give the narrator any

brilliant insight, just the fear that 'I'm going to die before my time' and

later lands him in jail where 'I killed a queen' (ambiguously worded so we

don't know if its a Royal or a man in drag - I'm hoping for the former). The

fact is everything achieved on whatever stimulation this is isn't real - so the

narrator needn't have bothered wasting his energy; the downside of 'Lucy In The

Sky' this is, proof that not everyone in the 1960s was swayed by drugs (we'll

ignore for now the fact that Crosby alone was responsible for turning half of

America on to them!) So many phasing effects have been added to this song that

it’s as if all the elements are taking place in some sort of fog – a neat

mirroring of the song’s ‘artificial energy’ in that the energy is real, it’s

the studio tricks that make it sound artificial on this song. A complete

one-off for The Byrds, this song features blaring horns and Clarke’s drumming

particularly high in the mix – one of Clarke’s most inventive parts, he

fittingly gets his only writing credit for a Byrds song because of it, as well

as for thinking up the song’s suitably blurry title. It's a strong start to a

strong album, already most unlike anything else the band have ever tried - or

will ever try again.

[74] Goin’ Back has its

fair share of fans and often features on CD-length best-ofs, but I have to

admit I’m not myself a fan of the Byrds’ rather dreary version. A rather drab

and slow arrangement of a rather drab and slow tune masks Goffin and King’s

actually rather clever and astute words and in album archive favourite Nils

Lofgren’s hands this nod to childhood is a happy, snappy wistful little song.

Here, like nearly all of the many cover versions of this song that exist, the

band sound as if they are singing themselves a lullaby to send them to their

childish sleep. I’m with Crosby on this one, who was partly booted out of the

group for the tantrum he had on the day of the recording, refusing to take part

in such an inane song until the Byrds’ production team physically barred him from

leaving until he’d sung his part. The harmonies are in fact the Byrds’ saving

grace – wistful and wise and yearning for simpler days – but you wish they’d

pick the tempo up just a little bit and get on with it. Still, there’s no

denying that this song’s simple but memorable lyrics deserve a better fate than

the shoddy version the band put together here. Unlike most of Notorious, this

track is neither daring nor beautiful.

The driving [75] Natural Harmony is a

Hillamn song that finally gives McGuinn the right setting to play with all his

futuristic toys. Roger also takes the lead vocal in a

rare act pof Byrds diplomacy and even treated with lots of feraky distortion

it's one of his better vocal performances too. The rest of the band (well, the

bits that were left) also back him up superbly, especially Hillman’s

mesmerising bass runs. The lyrics of the song sound more like Crosby’s work,

though, championing the hippie generation’s growing belief in nature and

natural order, experiencing what (so they believed anyway) their parents’

generation never had. The song’s chorus is the song’s secret weapon: goading on

his pursuers with the line ‘catch us if you can’, McGuinn’s narrator seems to

step into some sort of space-time continuum divide (hear this track and see

what I mean), stretching Columbia’s recording facilities to their limit. The

result is one of the more powerful songs on the album and new of the Byrds'

rare forays into all-out psychedelia: a world where mankind is in tune in an

awful lot bigger ways than just music. A neat crossfade brings us to...

[76] Draft Morning,a Crosby song 'rewritten' by the

others from what they could remember from an early recording (down to just two

songwriters they were stretching themselves very thin across 1968). 'Morning'

is

daring and beautiful all at the same time, an uncharacteristically tender song

about a favourite Crosby theme – mankind facing a choice between war and peace

and why they should choose the latter (it's also very similar indeed to what

Crosby's new pal Stephen Stills was up to in the dying days of the Springfield

with one of his best last songs for the band , the draft-dodging 'Four Days

Gone'). The band’s harmonies on the gloriously blissful verses - with Hillman

taking Crosby’s part - are never better than on this track, gliding peaceful

but eerily across the speakers in contrast to the trivial battle going on just

outside proper earshot in the middle section. A barrage of battle sound effects

competing with some of Michael Clarke’s hard-hitting drumming also conjures up

a particularly chilling scene, with Hillman’s bass holding it all together and

going for a bit of a stroll up and down the octaves as he does so. A CSN/Y

prototype in all but name, Crosby must have been fuming when the band decided

to hi-jack this partially recorded song after telling him to get lost,

re-writing many of the words in the process because they couldn’t remember

them! Out of all the great Crosby compositions around in late 67/early 68, this

is one of the least known but one of the greatest; even though it came with the

mixed blessing of re-writing most of the words, the Byrds obviously knew what a

good song this was too. The song would also have made a fine addition to the first

CSN album (Stills especially excelled on songs of draft dodging and melancholic beauty), ending with a lift from 'The Last Post' riff that sounds remarkably

similar to an idea nicked by Neil Young for the CSNY 'Freedom Of Speech' tour

in 2006.

The gentle lilt of [77] Wasn’t Born To Follow offers the usual conservative Byrdisan break

at this point in the album, a chance to take a breather from all that

psychedelic weirdness and go back onto firm hard land. Even in this

delightfully peaceful song about escape, rebellion and happiness, however,

there are some terrifically scary sound effects, mainly the loud distorted

phasing solo that comes out of nowhere and catches your breath for a few

seconds before disappearing again. Not one of this album’s better moments,

psychedelic effects aside, this song was still perfectly cast for use in the

1969 Easy Rider film, which legend has it was based loosely on

the characters of McGuinn (Peter Fonda) and Crosby (Dennis Hopper).

[78] Get To You ends the

side with a slight McGuinn song that once again veers from his two favourite

styles – gutsy country and psychedelic rock and roll. A simple tale of how the

narrator spent years trying to woo his missus and is excitedly waiting for her

on the next plane, the song even starts with a slamming door just to get us in

the right mood for the distance between the couple. This simple song develops a

new layer of meaning courtesy of the exquisite middle eight, however, which

explodes out of nowhere with strings, more psychedelic effects and some ‘vocal

percussion’ in the Pink Floyd 60s style. Is McGuinn singing ‘that’s a little

better’, ‘back to the garden’ ‘back to the better’ ‘back to the mountains’ or

something else entirely during this part of the song? No one’s ever been able

to tell for certain, probably including McGuinn.

[79] Change Is Now

might well be the highlight of the album, meshing a burbling bass and tight

guitar hook with some other-worldly vocals and space age lyrics. Another Byrds

song about the growing feeling of change in the air in 1967-68, the fragmented

lyrics are terrific and has there ever been a better line to sum up the 60s

than ‘change is now, all around, dance to the day when fear is unknown’?! The

restless tune is itself the perfect fit for this song about change and never

knowing what might be next around the corner but – being the Byrds – the past

and future sounds get a bit mixed up. Much of the song is based around the

band’s space-age past of experimentation (and features Crosby on guitar), while

the middle eight is more like the pure traditional country-style they are about

to embark on during the next album (future member Clarence White also makes his

present felt for the first time here). Hillman proved himself a master of going

in unexpected directions with his material on Younger Than Yesterday (this song is a close cousin of that album’s

stand-out track Thoughts And Words)

and this melody is one of his best, sweepingly psychedelic in the way it takes

us out into distant horizons but winningly cosy in the way it brings us back to

earth too. The slightly out-of-control McGuinn guitar solo - which is just

about crossing into feedback at the song’s end - and the gradually growing

growl of the bass which both suddenly break free of their moorings for a

second-half instrumental also constitutes perhaps the best 30-second burst in

The Byrds’ back catalogue, as the band slowly spiral up and up, reaching for

the stars and sounding like they make it too.

[72b]

Old John Robertson

may well be the last track the core quartet of the Byrds ever played on (that’s

Crosby back on harmonies and, unusually, bass). If so, then it’s a strangely

fitting track to end on, with Hillman’s lyrics about a social outcast who was

jeered at by his peers but may have possessed some great secret to life after

all fitting not only for Crosby’s acrimonious departure but Gene Clark’s as

well. Actually, Hillman is here remembering a figure from his childhood who was

dismissed for being weird but in retrospect seemed hyper-intelligent, unlocking

truths that Hillman could only now appreciate in the psychedelic age and the

bassist probably had no ulterior motive in mind when he wrote the song. In fact

this trick seems to have struck a chord with several musicians and is one of a

number of similar pieces written around this time by archive alumni (The

Monkees’ Mr Webster, The Hollies’

B-side Mad Professor Blyth, and

10cc’s Old Mister Time among them). The fact that this might be the last

‘proper’ Byrds recording until an un-mitigatingly awful re-union LP is a shame,

as Hillman’s joyous romping guitar riffs and McGuinn’s impassioned lead make

for an enjoyable few minutes. However, what the instrumental section with its

baroque string quartet solo (!) is all about I’m not quite sure (Hillman

memorably said in an interview that ‘we weren’t intending to use that kind of a

solo at all - these Salvation Army types just happened to walk into the studio

one day playing that solo when we were playing that track and it just seemed to

fit’ – although like many interviews with the Byrds in this period one senses

he was pulling somebody’s leg).

[80] Tribal Gathering is

another late-period Hillman classic, an atmospheric chant-like song whose

understated poetic verses are unnervingly simple until giving way to an

absolute sting of a guitar break that hints at the complexity behind the piece.

Another candidate for McGuinn’s best guitar solo, over several repeat

performances throughout the song it manages to tread a thin line between velvet

jazz and feedback blistered rock before finding its way back to the main tune.

The words are fascinating too and have been seized on by more than one music

author to sum up the changes happening in the mid-60s: ‘strange thing,

gathering of tribes…’ (more than one Byrds commentator reckons this song was

inspired by the crowds at the June 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, at which the

Byrds performed and in the brief film clip of which you can see McGuinn staring

at Crosby with a look of pure hatred during one of his politically provocative

outbursts). Tribal Gathering is very

sketchy but it does conjure up a very strong image of comparing the present

(and future) trends of youngsters to get together in groups, listening to music

and spreading their own creativity with their caveman ancestors, huddled round

a camp-fire telling stories. Even

though Hillman had composed more songs for the band than McGuinn and Crosby

combined by this point in the Byrds’ history, Hillman still hadn’t formulated a

compositional style anything like as distinctive as his fellow group members.

Here he takes his lead from McGuinn’s more futuristically-focussed arrangements

with the emphasis on sudden surging instrumental passages and Crosby’s

burgeoning hippie philosophy, based around wordy lyrics and strong harmonies.

The resulting typically Byrds-like mix is a quiet triumph and another album

highlight.

[81] Dolphin’s Smile

might be short – it clocks in at two minutes exactly – and it may sound like a

rough draft for Crosby’s later ocean-faring epics, but in many ways it’s a

landmark in Crosby’s writing, the first time he uses his familiar metaphor of

the healing powers of the sea. Using everything Crosby can think of that’s

spiritual and great about the ocean – and sounding mightily like the Beach Boys

in the process – he turns in one of the most poetic fragmented lyrics of his

career. Dolphin’s Smile is among the

lightest, prettiest songs the Byrds ever performed, even with another roaring

guitar solo from McGuinn near the end that seems to mirror the rather worried

verses, debating the scary future for America’s crystal-clear oceans. Like the

rest of the album, McGuinn passes up his more usual jangly 12-string

Rickenbacker for something much more expressive and it’s a shame that so many

later Byrds albums find him aping his early style rather than the fluid,

squealing sound he almost single-handedly invents here. As calm as a sea breeze

and as deep as the ocean, Dolphin’s Smile

is another of the album’s highpoints.

McGuinn gets the last word on the album in the

comparatively long (nearly 4 minutes, double the length of the last track) and

certainly comparatively weird track [82] Space Odyssey. With a

tune straight out of a sea shanty (a slowed down version of Jack Tarr, which the Byrds in fact go on

to cover on their 1969 Easy Rider

album) and lyrics that try a bit of fortune-telling about mankind’s future

progress, the song is a typical McGuinn track in that it tries to be everything

at once and only half gets away with it. Amazingly

McGuinn even guesses the imminent lunar landing wrong – ‘In 92 and 96 we ventured to the moon’ –

despite the fact that as a science buff he surely must have known preparations

were underway, with the landing less than 18 months after this album came out

(unless you believe the very convincing conspiracy theories that we never

really landed there of course – but that’s another website for another time…) You were a bit out there, McGuinn (in both

senses of the word!) Elsewhere the lyrics are equally dodgy and the tune

repetitive to the point of boredom and yet so thrilling are the synthesiser

effects and the burbling rocky guitar that you almost don’t notice. I’d also love to hear McGuinn revive this

song as the bare-bones ballad it’s crying out to be underneath all that

psychedelic clobber, as I bet it would sound even better! A strange

false ending – after a few seconds pause the synthesiser drifts in and out

again playing the song’s root chord – adds to the confusion of the listener.

In fact, confusion is a good word for this album all

round as its not quite clear what the Byrds are trying to do. Beautiful as much

of it is, pioneering as a good half of it might be, the Byrds - living up to

their ‘notorious’ title - have thrown just about every contradicting style and

lyrical theme they can into mix and yet somehow despite all that Notorious runs together beautifully, one

of the last great psychedelic artefacts from a near-perfect era even though I

haven’s got a clue what the hell most of it means. Not bad for a group falling

apart and it makes you wonder just what miracles the Byrds could have put

together in more stable conditions. Sadly the inspiration leaking out of nearly

every song on this album is not to be found again for a while in their back

catalogue. Once Chris Hillman checks himself off The Byrds’ flightplan and the

trimmed down band get on their country high horses, their albums gradually

become more and more ordinary and certainly far more unpleasantly schizophrenic,

veering from the old to the new clumsily and artlessly in a way that this album

does so beautifully and poetically. Read

on for the band’s one last moment of greatness when they finally get rid of the

trappings that dogged them long before the Notorious

years and finally set off for a brave new sunset….

A Now Complete Link Of Byrd Articles Available To Read At

Alan’s Album Archives:

'Mr Tambourine Man' (1965) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/news-views-and-music-issue-134-byrds-mr.html

'Mr Tambourine Man' (1965) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/news-views-and-music-issue-134-byrds-mr.html

‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ (1965)

http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2017/03/the-byrds-turn-turn-turn-1965.html

'(5D) Fifth Dimension' (1966) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/news-views-and-music-issue-49-byrds-5d.html

'(5D) Fifth Dimension' (1966) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/news-views-and-music-issue-49-byrds-5d.html

'Younger Than Yesterday' (1967) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2011/08/news-views-and-music-issue-108-byrds.html

'The Nototious Byrd Brothers' (1968) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/review-20-byrds-notorious-byrd-brothers.html

'Sweethearts Of The Rodeo' (1968) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2014/06/the-byrds-sweetheart-of-rodeo-1968.html

'Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde' (1969) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/news-viedws-and-music-issue-68-byrds-dr.html

‘The Ballad Of Easy Rider’ (1969) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/the-byrds-ballad-of-easy-rider-1969.html

'Untitled' (1970) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/review-38-byrds-untitled-1970.html

'Byrdmaniax' (1971) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/the-byrds-byrdmaniax-1971-album-review.html

‘Farther Along’ (1972) http://www.alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/the-byrds-farther-along-1972.html

'The Byrds' (1973) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-byrds-1973.html

Surviving TV Appearances http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-byrds-surviving-tv-appearance-1965.html

Unreleased Songs http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-unreleased-songs-1965-72.html

Non-Album Songs

(1964-1990) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-non-album-songs-1964-90.html

A Guide To Pre-Fame Byrds

Recordings http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-pre-fame-recordings-in.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part One (1964-1972) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part Two (1973-1977) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums.html

Solo/Live/Compilation Albums Part Three (1978-1991) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_9.html

Solo/Live/Compilation Albums Part Three (1978-1991) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_9.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part Four (1992-2013) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_16.html

Essay: Why This Band Were Made For Turn! Turn! Turn!ing https://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/byrds-essay-why-this-band-were-made-for.html

Essay: Why This Band Were Made For Turn! Turn! Turn!ing https://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/byrds-essay-why-this-band-were-made-for.html

No comments:

Post a Comment