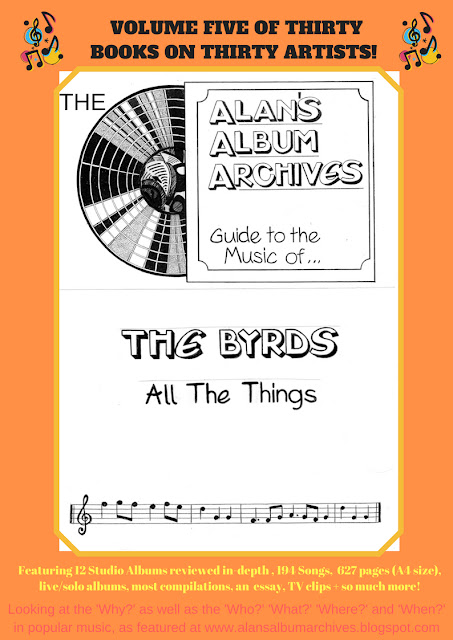

You can buy 'All The Things - The Alan's Album Archives Guide To The Byrds' by clicking here!

The Byrds “5th Dimension” (1966)

5D (5th Dimension)/Wild Mountain Thyme/Mr Spaceman/I See You/What’s Happening?!?!?/I Come And Stand At Every Door/Eight Miles High/Hey Joe (Where You Gonna Go?)Captain Soul//John Riley/2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jet Song)

The Byrds weren’t exactly flying at high altitude by

the time 1966 rolled around. Never the most stable of bands, as early as this

third LP and second year they’d lost their lead singer-songwriter Gene Clark

and like many pre-psychedelic bands in 1966 were split between embracing all

the new exciting possibilities that laid over the horizon or to make music that

their grannies would really enjoy. This sort of confusion occurs many times on

Byrds LPs – they even name their 7th album ‘Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde’ in

reference to this split personality – but this third record is the first time a

Byrds LP is so eccentric that you truly don’t have a clue what’s coming next

the first time you play it. Without Gene Clark there to take the lion’s share

of the writing credits, the Byrds truly don’t know what direction to fly off in

next – so what we get are a few traditional folk songs that if anything sound

slowed down rather than jazzed up, a blues instrumental, some deeply serious

protest songs, some wild and wacky protest songs, a truly adventurous

psychedelic single in ‘8 Miles High’ and its often-overlooked successor ‘I See

You’ and, umm, Roger McGuinn’s hoover doubling as a Lear Jet. Even given that

it was 1966, this album is weird.

But as ever on this website, being ‘weird’ doesn’t

being ‘bad’. As a general rule it’s the bland and empty albums (and artists)

that tend to get short shrift from us (anybody mention The Spice Girls?!) –

albums this weird and eccentric are well worth a place in our discography, even

if this album’s just a little too lop-sided to make it into the 'AAA top

albums' list proper. So here’s the story of The Byrds’ nest-egg, the album that

more than any other sets the template for the group in the years to come and

each character’s later solo records to boot – McGuinn’s quick-switching between

heavy world philosophy and light as a cloud comedy; David Crosby’s first

stirrings of outrage at the corruption in the world around him and the

miserable use humans have made of all the things they’ve been granted in life;

Chris Hillman adds a touch of soul alongside his more usual touches of country

and bluegrass; and drummer Michael Clarke just plays the drums.

But no, that’s being unfair – its as a band playing

together that The Byrds really grow on this record and Michael Clarke’s

contribution to that is the greatest of all. Let’s not forget, The Byrds had

never actually played as a five-piece in the studio until the session after ‘Mr

Tambourine Man (which in terms of instruments just features McGuinn alongside a

set of session musicians) in 1965 and the band were understandably a little rusty

on the first two albums. But by the time of 5D The Byrds are suddenly a

powerhouse of noise, easily the equal of their more rocky counterparts in 1966,

but still with enough subtlety to handle the ballads and switches of tempo

convincingly. Michael Clarke, the Byrd who was famously chosen for his perfect

blonde haircut rather than his musicianship skills and learnt to play the drums

on cardboard boxes, is no longer an embarrassment to the band’s sound but one

of the best drummers around. His switches of style are amazing on this album – he

so should have been a 'jazz' not a rock or pop or even folk-rock drummer - equally

at home with the improvisational licks of ‘8 Miles High’, the all-out rock of

‘I See You’ the truly tricky slowed-down beat of ‘I Come And Stand At Every

Door’ and the pop of ‘Mr Spaceman’. It's when he's being made to play the same

licks several times in a row his playing suffers. So huge is this leap that I

assumed for years the Byrds had brought in a session drummer for this and the next

two albums but no: every drum note and cymbal wash is indeed played by Michael

Clarke. And even if the other Byrds did allegedly spend hours telling him what

to play I don’t care – he still had to play it. Possibly the biggest leap in

any AAA musician’s abilities come in this record, which remains Michael

Clarke’s greatest (half) hour.

Not that the other Byrds are far behind him. Freed,

temporarily, of playing along to both Gene Clark’s and Bob Dylan's lyrical songs

(the band are really making the most of this opportunity to create a 'new'

sound well away from what they were known for - it's a temporary solution,

though, with Dylan very much back in place for the nect LP), the other three

Byrds are given much more scope to put their instrumental skills to use. And,

barring McGuinn’s even briefer attempt at trying to write lyrical passages like

his colleague Gene, the other songs on this album are all rhythmically driven

rather than lyrically driven (if the Byrds really were formed to be the halfway

point between Dylan and the Beatles then this is the point where the fab four

influence really takes over and folk becomes just another wash of colour

rather than a driving force). McGuinn’s guitar playing really leaps forward on

this album, especially the first recording (!) ‘8 Miles High’, adding

psychedelic fringes to what had previously been a very clear and folky sound.

David Crosby, whose roots lay more in jazz and Indian music than pop and rock

in this period, finally manages to weld his four loves together during this

period, with both lead Byrds turned on by the freedom this offers (McGuinn

sounds like nothing less than Ravi Shankar playing the guitar in this period,

although its Crosby’s rhythm playing on ‘8 Miles High’ that’s probably as close

to jazz as we’re going to get in a rock and pop format). Chris Hillman doesn’t

get much to do yet – surprisingly, given that his more country style and

song-writing is all over follow-up LP ‘Younger Than Yesterday’ – but his bass

playing, too, is showing a definite Beatles influence in this period, playing

the less obvious bass chords throughout each song. For one of only two albums

this the classic line-up of The Byrds actually playing as a band, each bringing

their own styles to the table and creating something new out of their combined

efforts. 5D is nothing like as cohesive and easy to listen to as ‘Younger Than

Yesterday’, but it is the point at which the Byrds truly do add another

dimension to their playing and writing, breaking through with a pioneering sound

that still sounds unique to this short span of albums.

It's a real shame, though, that Gene isn't here. The

most sensitive Byrd, the one who strove for new experiences and turned

suffering into art would have been a real asset on an album that's all about

exploring both yourself and the world around you. Gene had simply burnt himself

out, taken too much criticism to heart (his colleagues, jealous of the extra

money he roped in from songwriting royalties didn't help), lost his identity in

a sea of screaming girls and clashing wgos and couldn't cope with the stressful routines of being a rock star

(being famous is usually fairly glamorous nowadays, with albums every few years

in a relatively stable market where your fans remember you and come back again

for more after a mutual rest - in the 1960s fame was a stepladder that had to

be continually climbed with the goalposts forever moving further away). Things

came to a head when Gene, like Brian Wilson before him, found himself locked on

yet another aeroplane pointing in a direction that led anywhere but home, the

four small claustrophobic walls a symbolic metaphor of the fame he felt was

trapping him from all sides. Crosby will go on to smirk at the irony of a Byrds

being scared of 'flying' in the unreleased song 'Psychodrama City' taped at

these sessions ('I don't know why he got on at all if he really didn't want to

fly!' he cackles, about both the physical flight and Clark's pursuit of fame

with the band). But like Brian the year before, poor Gene didn't break down

because of that flight but because of the years of constant touring, competing,

writing, recording, promoting, worrying, arguing and nagging doubts of the past

few years; at least Brian had his brothers to turn to - in The Byrds it was

every man for himself and as the band's biggest star in the early days (in a

songwriting sense at least) Gene felt the loneliness at the top more than most.

From here-on in his is a sad tale of wanting and needing fame and recognition,

the demons of guilt and fear that such fame and recognition awakened and

unhappy slumps back into obscurity, punctuated by increasing drug and alcohol

addictions. Gene was a born rock star, but with the constitution of a poet that

was going to see him eaten up in any band - unlucky for him he became a Byrd, a

band who by rights should have been named 'The Piranhas'.

'5D' is generally seen as the album where the other

Byrds step out from under Gene's shadow. By and large that's true, but for now his shadow is just too big to match. Gene

still had time to leave the mother of all leaving presents: the lyrics for

'Eight Miles High' and an excellent harmony vocal on flip-side 'Why?' (a Crosby

song senselessly left off this album and re-recorded to lesser effect for

'Younger Than Yesterday'). Both songs rather set the tone for the biggest album

theme of unlimited horizons and a new sense of understanding of the world. Both

Crosby and McGuinn - the two chief writers on this album though all four

remianing Byrds receive a credit for instrumental 'Captain Soul' - found

themselves at an unusually harmonious point of view, albeit from two very

different resources. Crosby has just discovered drugs, his mistress muse and

ultimately biggest monster that will gain gradually more and more control over

his life until the point in the mid-1980s when a judge locks him away in a

state prison as one last desperate attempt to save his life. For now, though,

drugs have done wonders for Crosby's pscyhe: they've expanded his point of view

to such a point that he truly discovers his 'voice'. The political 'What's

Happening?!?!?' is far from the best song he'll ever write, but it's a crucial

breakthrough for him as a composer, daring to ask why a mad world is quite as

mad as it is. His lyrics for the 'Eight Miles High' soundalike 'I See You' also

point to new realisations, with a whole host of seemingly unlinked metaphors

spinning into his mind each time he sees a 'girl'.

McGuinn, meanwhile, is spending his last album as

plain 'Jim' McGuinn - he's become increasingly fascinated with the Subud

religion (someone influential in the cult told McGuinn he was unlucky because he

had the 'wrong' number of syllables in

his name - asked to pick a name with two syllables he chose 'Roger'; this led

to a joke/hype/conspiracy theory on the lines of the 'Paul is Dead' theory that

he'd been 'replaced'. When asked once by a hapless reporter what had happened

to his 'twin brother Jim' McGuinn joked that he'd 'gone to Rio' - the story

behind the rather peculiar title for his 1990 'comeback' album!) Many people

assumed drugs was the cause behind Roger's change of both name and personality,

but no - McGuinn kept as far away as any rock star in the 1960s could (natural

cautious, perhaps he'd already seen how the head-first Crosby had been affected

by them). Religion and books (especially science ones) and the need to 'fill

the gap' left behind by Gene Clark all conspired to create a McGuinn who was

far more on the ball and sure of himself than on the band's first two albums

(he jokingly calls the Byrds' music 'philoso-rock' during the period interview

hidden away on the CD re-issue). The title track, a debate about the many

different dimensions of length, height, space, width and time that can be

experienced by people was perfect for the times and deserved to be one of the

band's bigger hits. 'Mr Spaceman', meanwhile, is a trippy comedy song about

extra-terrestrials - the first appearance of a favourite topic that's going to

run his songs for years, through 'CTA-102' and into 'Space Odyssey' on the

next two Byrds albums. His choice of cover song, the world war two protest song

'I Come and Stand At Every Door' is also a significant choice - though Crosby's

later rants against the Vietnam war and contemporary politics embarrassed him

(Roger thought 'rock' stars should be separate to such things), McGuinn had a

passion for using songs from the past as warnings to us in the present about our

future - a theme that runs through all his 'Folk Den' revival projects in the

21st century and right back to 'We'll Meet Again' and to some extent 'Oh Susannah'

from the first two albums. This is his best choice yet, the seven-year-old

ghost of a victim of Hiroshima doomed never to know what it's like to grow old

and looking down heartbroken at a world that should have been hers to grow up

in (McGuinn is at his best on this song, the emotion of the song breaking even

his famously ice-cold persona).

Unfortunately, letting each style take over one at a

time means that this is a truly uneven record at times. The rest of the album

songs are at best filler, at worst desperation: while not every track on 'Mr

Tambourine Man' or 'Turn! Turn! Turn!' was a knockout, you could at least hear

that the band were trying something that could have worked or nearly worked

(yep, even 'Oh Susannah!') '5D' is much more of a rollercoaster ride though:

alongside 'Eight Miles High' 'I See You' '5D' 'I Come and Stand' and 'What's

Happening' are two fairly dreary traditional folk songs (seemingly recorded

because the band feel they havcen't done much folk on this album), even

drearier Stax soul pastiche 'Captain Soul' and the sound of McGuinn's hoover

doubling as a lear jet while the band use some random sound effects and sing

'go round the lear jet, baby' over and over. Credited to McGuinn, this song

makes you feel that if he wasn't taking drugs then perhaps he should have been

- even by Byrds standards (who always try and end their albums on an unusual or

at least eccentric song) '2-4-2 Foxtrot' is a novelty unbecoming of their great

name. Personally I quite like 'Hey Joe', the cover that everyone wqho owns this

record seems to despise, but even though Hendrix re-wrote the rule box on

revisiting folk tunes with this very song, Crosby's earlier versions is fun,

funky and got there first (Hendrix learnt the song from the San Franciscan band

The Leaves - they learnt it from Crosby, who was their early champion!)

The oddest thing about '5D' is that while the

material is (by and large) in place (give or take the sound of a vacuum cleaner

and a folk song or two), this just doesn't 'sound' like an album from 1966.

Released a mere month before The Beatles' 'Revolver', the two records couldn't

be more different: there's no unusual sounds on display here (except that dang

hoover!), no sitars (odd given that Crosby and McGuinn had been partly responsible

for encouraging George Harrison's interest in it, famously teaching him how to

play on a beaten up old instriment in a bath-tub on a rare get together in a

hotel room - the only place quiet enough away from reporters!), no tape-loops,

no sound effects and with the exception of the deeply traditional sounding

'Wild Mountain Thyme' and 'John Riley' no strings or brass. Everything on the

album could be replicated in concert, even though the Byrds weren't doing much

touring at all that year (they won't do thatmuch touring again until McGuinn

reforms the band in late 1968). In fact take 'Eight Miles High' and copycat 'I

See You' plus the title track and 'Every Door' away and '5D' isn't even a

complex album - Gene Clark's lyrics alone made those two albums seem deeper

than '5D', which at times seems overtly childish ('Mr Spaceman' is a comedy

song; 'What's Happening?!?' shares a simplistic world view, '2-4-2 Foxtrot' is

a novelty and 'Captain Soul' the kind of things children learn as scales when

practising an instrument).

Ultimately '5D' is a strange experience. The

'difficult third record' for The Byrds, it's not as satisfying as either of the

folk-rock first two or as pioneering and consistent as albums four and five.

If the Byrds’ first two albums were the TV equivalent of ‘newsnight’ or

‘panorama’ (meaning well but a bit fusty and old-fashioned and a bit too

earnest in getting messages across), this album is a TV sketch-show, switching

gears so suddenly it makes us gasp (although like even the worst sketch shows,

if you don’t like one particular style another will be along in a minute). However

when this album is good it's exceptional, showing off every one of the band's

strengths post-Clark: Indian-influences, classy harmonies, quirky lyrics and

unsettling ideas and at times reaches unbelievable peaks. Like the ‘magic

carpet’ the band appear to be sitting on, the journey is a curious mix of the

old-fashioned (this is a rug that looks like an antique after all), the

then-modern (the band are eating fast-food – or at least they are on the back

cover) and the mystical (just check out David Crosby’s new fringe jacket –

he’ll be wearing those non-stop for the next 10 years!) Crossing many borders,

melting several boundaries, 5D is one hell of a ‘trip’ but there's a few crash

landings during take-off too. That's what happens when you take your rides from

a band as wild and exciting as The Byrds who can show you some of the most

amazing sights you'll ever see.

The

Songs:

First up is the title track [46] '5D (Fifth Dimension). I

must confess I never used to be that keen on this song, the first track on the

first Byrds album I ever owned, but over time its as good an introduction as I

could hope to have, poised between the band’s folkie past and their psychedelic

future. It’s completely unlike anything Roger McGuinn will ever write again:

its poetic imagery and carefully constructed lengthy phrases sound more like a

Bob Dylan or Gene Clark song (or the best fit of all, the book of the

Ecclesiastes set to music that was ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’) and has the kind of

tune that sounds as if its been around for generations. But lyrically it all

gets a bit more confusing: the talk of discovering a ‘new dimension’ to life is

common speak amongst 60s drug takers but its part of a large parcel of mid-1966

songs that don’t actually come out and say it quite yet (The Beatles’ ‘Dr

Robert’ and ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’ are two more examples). Traditionally

when bands do this kind of thing they couch the music with the most

exhilarating, breathtaking and groundbreaking music possible – but not here;

The Byrds are instead treating this new discovery as one on a par with their

gospel/traditional music, going back to their roots in order to express what a

change this stepping stone in their lives represents. The best juxtaposition on

this track, though, must surely be the line about ‘I saw the great blunders my

teacher had made, sicnetific delirium madness’ which occurs at the most

traditional part of the whole track, just as the barbershop vocals kick in –

borrowing from bygone generations at the same time Mcguinn’s narrator promises

the same won’t happen to him and his kind! McGuinn’s vocal is the best thing

about this track, with just the right sense of awe and curiosity (indeed, it

might be his best vocal of all on a Byrds record) and his lyrics are

particularly strong on this song, making it a shame that he never wrote more of

these songs, swapping its style for all-out country or rock and roll on later

tracks. Yet, even though it’s a song I admire, it’s a song that’s hard to love

and is ultimately uninvolving somehow – it’s very hard to ‘connect’ with this

song despite its tales of new adventures, perhaps because of its

backwards-looking melody and style. Never mind, the band will get it spot-on for

‘8 Miles High’. In yet another Byrds-Beach Boys crossover, that's future Smile

lyricist Van Dyke Parks guesting on organ (McGuinn apparently told him to

'think of Bach'!)

[47] ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’ is a lesser attempt at the folk trick that

works so well later on in the record during 'John Riley', a slightly boring

song that, like many of The Byrds’ worst arrangements, is slowed to a crawl.

One of the more boring songs in The Byrds’ canon, this features another jaded

string arrangement sitting in counterpart to McGuinn’s rather lumpy guitar work

and is only truly saved by the harmonies, with Crosby’s falsetto shining out

loud and clear as ever. Lyrically this traditional folk song is a rather odd

piece, telling us that as long as the mountains exist there will always be a

love to replace the one you’ve just lost (mountains usually signify permanence

when used as metaphors for songs), although this might make sense of yet

another battle going between the band’s usual instrumentation and the more

folkie harmonies/strings. A curious misfire this one, seeing as its built on

many of the things that traditionally work well in Byrds songs.

[48] ‘Mr Spaceman’ is a much more crafted song and travels along at a

fair lick, but like many of McGuinn’s lesser songs its repetitiveness is

extremely irritating and it takes five or so verses to basically tell us the

same thing over and over (this song must have the biggest chorus repeats of

pretty much any song that clocks in at just over 2 minutes!) At least the

lyrics are funny, though (well sort of, once) with an alien beaming up

McGuinn’s narrator into his spaceship and showing him around before taking off

again ( Something that’s hard to grasp for modern newcomers to this song – yes

the ‘spaceman’ in the title is an alien not a man in a spacesuit because most

people didn’t really think of humans as being in space before 1969 and the

alleged moon landing; we knew that aliens might have the potential to visit us

back then, but not that we had the potential to visit them) and contain a

lovely line in Mcguinn’s mournful ‘I hope they get home alright’, as if he’s

just waved goodbye to his folks on a long drive home instead of a species

taking over his planet from the other side of the world. Really, though, this

song is too chirpy for its own good and like many of the band’s comedy songs

falls flat, because the humour’s too dry for us to be sure that it really is

humour we’re listening to (a similar thing happens with 1967’s ‘So You Want To

Be A Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’, which is the story of X Factor 30 years early – the

world should have heeded the warning!)

[49] ‘I See You’ is the next

strongpoint on this album, a rare McGuinn-Crosby collaboration that shares so

much DNA with ‘8 Miles High’ that its surely a long-lost twin. We get the same

frenetic drumming, the same Coltrane-inspired rhythm guitar, the same

completely off-the-wall Rickenbacker solo and the same fragmented and cryptic

lyrics. The biggest difference is the subject matter – if 8 Miles High is about

experiencing the world afresh (see below), then song is about discovering

people fresh and truly seeing what they’re up to for the first time. This song

is pure chaos from first note to last, all tied together with glittering Crosby

harmonies, with some classic lyrics that take in honesty and lies, love and

infatuation, past lives (the first appearance of this well-loved and by 1970

well-worn Crosby theme) and earth and space, all dealt with in fragmentary,

image-filled lines. A terrific launching pad for a song about new experiences

and finding out more about life The Byrds really go to town with this record,

making it more raucous and energy-filled than anything in their back catalogue

(barring, of course, the recently-recorded ‘8 Miles High’). Long dismissed as a

poor man’s 8 miles of altitude, this is actually a pretty good second take on a

similar subject and well worth digging out by all the many people out there who

consider ‘8 Miles High’ one of the best records of the mid-60s.

[50] ‘What’s Happening?!?’ is Crosby’s big breakthrough. It’s

actually his first full songwriting credit on any album (although the pre-fame

Byrds CD ‘In The Beginning/Preflyte’ has one other) and it really sets the tone

for just about everything Crosby’s written afterwards. A series of rhetorical

questions that at first appear to be dissing some jilted lover but then end up

being a rant about the faceless rich who run society without consultation with

the other people in it, this is Crosby waking up to how the world works and

putting into a place an anger and rage that still simmers through his work

today. While the song sounds unfinished by his later standards (Crosby’s songs

more or less give us comfort, as well as telling us how hard it is to change

the unchangeable), another strong recording makes up for any lapses in the

song, with McGuinn’s heavily echoed guitar seemingly answering Crosby’s cries

after every line. By 1966 standards this song is hugely impressive – when

everybody else was telling love stories of one kind or another, Crosby was

already asking ‘Why?’ (a question that’s taken up with a track on the next LP)

and unlike the small handful of tracks on this theme that had appeared in the

past, this song doesn’t even try to offer answers, it just shrugs its head and

moves on.

The tracklisting that puts that track right before

[51] ‘I Come And Stand At

Every Door’ is a masterstroke. An old 1940s song written in the

aftermath of the Hiroshima bomb, this is another angry song that demands

answers from the people in power and in the context of this most 60s of records

seems to be the hippie generation distancing themselves from the ‘war

generation’ of their parents. In many ways this Nazim Hikmet song (translated

by Pete Seeger and also covered by Stephen Stills’ later girlfriend Judy Collins)

is the first 1960s song, using the ghostly apparition of a murdered

seven-year-old to plead that the atom bomb is never used again. Indeed, its

amazing this very then-topical song hadn’t been covered by a rock and roll

group before – its only 3 years since the Cuban Missile Crisis after all and

the worries over the Cold War with Russia are all over this list, right up

until the fall of communism in 1989. McGuinn’s subdued vocal is another of his

best, undermining all sense of drama and emotion with its vicious one-note

stabs at the unseen attackers. Interestingly, it’s not until the second verse

that we learn the narrator is a ghost from Hiroshima (pronounced with the ‘old’

Western phonetic spelling heeeero-sheema – it was years before I realised those

talking about ‘heroshimah’ were on about the same thing) and they could stand

for any nation under attack till then. It’s also interesting that Hiroshima is

already considered to be ‘long ago’ by 1966 (21 years on) – could it be that

The Byrds were trying to make a statement here to last for centuries? The band

performance is another one that’s top notch: Clarke’s general drum rumble

intercut with sudden bangs on the drum kit sounds like its being played in slow

motion, while the echoey Rickenbacker guitar truly does sound ghostly here.

Perhaps this is the 5th dimension the Byrds are on about in the

title – not the brave new world of exciting psychedelia but the old unseen

phantoms that haunt mankind throughout his history until he learns to change

his ways.

Next up is [52a] ‘Eight Miles High’. Where do I start with this

track? It’s so well known that everyone assumes it was a #1 (actually it was a

comparative flop, especially in Britain where a radio ban for ‘drug-addled

lyrics’ meant it barely went top 40) but it’s probably more important for the

songs it influenced rather than for itself: I doubt we’d have had other

psychedelic journeys like ‘I Can See For Miles’ and ‘Lucy In the Sky With

Diamonds’ had this track not come first to break the mould. Gene Clarks’

farewell present with the set of lyrics for this song are first class: so

fragmented they sound like a haiku poem but together with the pounding music

they sound like a catalogue of last images seen before the coming of something

either exhilarating or destructive. The band’s playing is as tight as can be,

with Hillman’s bouncy bass rooting the song magnificently, before Crosby’s

scratchy and angry rhythm guitar chips away at the song and McGuinn’s

Rickenbacker soars on top. You can hear a first take of this song on the

current CD release and the difference between the two is like night and day

(the first is even creepier, mainly thanks to a slower tempo and an even more

out of control guitar part), showing just how important this song was to the band

that they re-recorded it again later to get it right. A word about the lyrics:

every fan knows it was really about The Byrds’ ill-fated trip to London (the

one where they were under-rehearsed, billed as ‘America’s answer to The

Beatles’ and got roundly booed at most of the shows), but the lyrics about

‘rain gary town, known for its sounds’ was about London and the line about ‘in

places small faces alone’ may well be about another AAA group just starting in

1966... Marvellously cast between being in control and falling over the edge of

a cliff, this is the last definitive Byrds song for some four years, mixing the

past and the future sound of music like never before. And to think, just a few

decades after this we get The Spice Girls as the default mode...

Most fans hate [53] ‘Hey Joe (Where You Gonna Go)’, seeing it as a

poor relation to the Hendrix version. But what few people know is that Hendrix

would never have known the song had Crosby not ‘discovered’ it (his protégé

band ‘The Leaves’ covered it first, although this Byrds recording is after

Hendrix). People seem to hate the fact that the band play it fast rather than

slow, but that’s how the song was written – and to my ears it sounds just as

good, if not better. Unfortunately, good as the arrangement is, this is

obviously a first take or as good as; the band sound tentative and aren’t sure

whether to really go for it or not right up to the curious way the song fizzles

out at the end. Crosby’s vocal – only his second lead in the band’s released history

– is nicely strong I think, even if he treats the whole thing like a game

rather than life or death. The only real problem with this song is that it’s

basically the forthcoming ‘Captain Soul’ all over again with some added lyrics

and taken at a slightly faster trot – and guess what song came next in the

track-listing?!

[54] ‘Captain Soul’ is another of this album’s pot-pourri in styles

that doesn’t quite come off. Too rocky for soul, with too many psychedelic

twinges, this song simply sounds like a studio jam built on a promising Hillman

bass line (that’s the most soulful thing in this song, sounding rather like a

Booker T riff) that features a lot of uninspired dross, really, barring the

rather impressive harmonica part (played by a returning Gene Clark who was

visiting the session, but sadly doesn't get a credit on the sleeve!) According

to the sleeve-notes, this song was Michael Clarke’s idea, something which is

surprising given that his rather clichéd drum pattern here is the most bored he

sounds across the whole album! The song was originally called ’30 minute

break’, by the way, and was recorded in a, umm, 30 minute break between other

recordings (although my sessionography suggests they weren’t actually doing

anything else that day) after the band developed the song from a jam session

playing Lee Dorsey’s hit ‘Get Out Of My Life, Woman’. Not that you’d know that

from the finished product which sounds very, well, cautious. What is it with

bands wasting their time on soul-inspired jam sessions in this period? (The

Beatles were recording their ’12 Bar Blues’ during the Rubber Soul sessions at

virtually the same time this track was recorded).

[55] ‘John Riley’ is, like ‘Wild

Mountain Thyme’, a traditional folk tale of a sort the Byrds never really tackle

again, this time two songs from the end instead of two from the beginning – in

fact, it sounds more like a Pentangle track! But Mr Riley is more successful

than his cousin, thanks to the battle royale going on between the band’s more

traditional guitar-bass-and-drums line-up on the left speaker and McGuinn and

Crosby’s etheral harmonies and a rather stilted string arrangement in the

right. Hillman’s bass is terrific on this track, copying Mcguinn’s guitar in

parts before taking off for his own wander up and down the octave, mimicking

the mournful girlfriend ever-searching for her partner lost to the sea. The

band’s harmonies are well suited to this song (especially the last verse, where

Crosby plays out the drama in counterpoint to McGuinn’s more detached lead) and

it’s another interesting stepping-stone from the Byrds’ folk past to their

out-and-out psychedlic future.

Last up comes one of the weirdest tracks ever to

grace an AAA album. In fact, so unintentionally hilarious is [56] 2-4-2 Fox Trot (The Lear Jest

Song) that I was tempted to put it among my favourites. In keeping with

this album’s theme of travel and ‘space’, the album ends with a pilot running

off a list of things to check on his machine while The Byrds repeat ‘going to

ride a lear jet, baby’ over and over the song’s repetitive riff. The Byrds chant in the middle, some

idiot reading flight instructions in the left speaker. Best of all, the band

discovered late in the day that they would not be able to record any real sound

effects of a ‘lear jet’ but McGuinn decided to save the day by announcing that

his new space-age vacuum cleaner sounded just like an airplane taking off (it

doesn’t, it just sounds like somebody’s just started vacuuming in the house

next door – honestly, guys, you could at least have trimmed the opening section

where somebody turns it on!) How did they think they could get away with this?!

For once, even the excuse ‘well, it was the 60s – it was all new then’ sounds a

bit hollow. The result is one of the funniest recordings of them all – but in

the context of this brave album its a sad low spot to go out on, right up there

with ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’s ‘Oh! Susannah’ as ‘last track on an album you never

ever want to hear again’.

So, not every ‘trip’ this magic carpet of an album

takes us on is successful. Sometimes you have to scratch your head and ask what

on earth was going through the band’s minds that they thought they could get

away with us. But then again, it’s amazing that there are any decent tracks on

this album at all – having lost their lead writer Gene Clark and decided to

forgo Bob Dylan songs for the foreseeable future (well, until the next album at

least!), the bulk of this album is left to McGuinn and Crosby to fill, a pair

of writers who had only managed 5 co-writes between them on Byrds albums total

by then and they do so admirably, setting the templates for much of their music

to come. If 5D is disappointing in many ways for an album that promises so much

about taking us to ‘new dimensions’, in the context of The Byrds’ back

catalogue its quite a revelation, marking the stepping stone where the band

went from being a Gene Clark showcase with some nice Rickenbacker to being a

fully fledged rock outfit who could sit comfortably amongst their

contemporaries. 5D is not the best album from the magical year that was 1966

you will ever hear – but individual tracks are right up there with the best

that music had to offer in that halcyon period.

A Now Complete Link Of Byrd Articles Available To Read At

Alan’s Album Archives:

'Mr Tambourine Man' (1965) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/news-views-and-music-issue-134-byrds-mr.html

'Mr Tambourine Man' (1965) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/news-views-and-music-issue-134-byrds-mr.html

‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ (1965)

http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2017/03/the-byrds-turn-turn-turn-1965.html

'(5D) Fifth Dimension' (1966) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/news-views-and-music-issue-49-byrds-5d.html

'(5D) Fifth Dimension' (1966) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2009/11/news-views-and-music-issue-49-byrds-5d.html

'Younger Than Yesterday' (1967) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2011/08/news-views-and-music-issue-108-byrds.html

'The Nototious Byrd Brothers' (1968) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/review-20-byrds-notorious-byrd-brothers.html

'Sweethearts Of The Rodeo' (1968) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2014/06/the-byrds-sweetheart-of-rodeo-1968.html

'Dr Byrds and Mr Hyde' (1969) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/news-viedws-and-music-issue-68-byrds-dr.html

‘The Ballad Of Easy Rider’ (1969) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2012/09/the-byrds-ballad-of-easy-rider-1969.html

'Untitled' (1970) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/review-38-byrds-untitled-1970.html

'Byrdmaniax' (1971) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/the-byrds-byrdmaniax-1971-album-review.html

‘Farther Along’ (1972) http://www.alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2013/04/the-byrds-farther-along-1972.html

'The Byrds' (1973) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-byrds-1973.html

Surviving TV Appearances http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/the-byrds-surviving-tv-appearance-1965.html

Unreleased Songs http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-unreleased-songs-1965-72.html

Non-Album Songs

(1964-1990) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-non-album-songs-1964-90.html

A Guide To Pre-Fame Byrds

Recordings http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-pre-fame-recordings-in.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part One (1964-1972) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/02/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part Two (1973-1977) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums.html

Solo/Live/Compilation Albums Part Three (1978-1991) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_9.html

Solo/Live/Compilation Albums Part Three (1978-1991) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_9.html

Solo/Live/Compilation

Albums Part Four (1992-2013) http://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-byrds-sololivecompilation-albums_16.html

Essay: Why This Band Were Made For Turn! Turn! Turn!ing https://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/byrds-essay-why-this-band-were-made-for.html

Essay: Why This Band Were Made For Turn! Turn! Turn!ing https://alansalbumarchives.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/byrds-essay-why-this-band-were-made-for.html

Re: "I Come And Stand At Every Door"

ReplyDelete"Indeed, its amazing this very then-topical song hadn’t been covered by a rock and roll group before"

In fact the 'song' was a poem which was put to music by several people. Concurrent with the Byrds version, The Misunderstood used the same lyrics in their song "I Unseen" recorded in 1966. I don't know who recorded first, but the Misunderstood version stayed in the can until 1969.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Misunderstood_discography

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N%C3%A2z%C4%B1m_Hikmet#cite_note-albany.edu-26

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mzs7KqAT6pE

Almost! When the poem was 'performed' it was chanted - I believe the song was adapted from the 'music' or at least the rhythm used during the chanting. From one thing I've read The Misunderstood started doing their version after hearing this LP, but I didn't mention it in the article as I haven't seen enough sources to confirm it yet. 8>)

ReplyDeleteHi Alan

ReplyDeleteI did a bit more research. On the CD "The Lost Acetates" (Ugly Things UT CD 2201) there are two versions of "I Unseen". Neither match the version on "Before The Dream Faded" (Cherry Red). The Sleeve notes of Lost Acetates read (in part)

'Three weeks later on January 11, 1966 they recorded three more songs, including ... Interestingly they also laid down an early version of a song they would rerecord in London: 'I Unseen'. The song originated with a poem by Nazim Hikmet written from the point of view of a seven year old child killed in the atomic blast at Hiroshima; Rick Brown had discovered it on a Pete Seeger record. Hikmet's poem was combined with a riff composed by Steve, which Greg played on...'

[elipsis indicates cuts]

Later on:

On Sept 7, 1966 ... Finally, 'I Unseen' received a complete makeover, the powerful lyrics now amplified by a louder faster arrangement, including a completely revamped bridge section supplied by Tony Hill.

Assuming the sleeve notes are accurate, they could not have not have heard Fifth Dimension (which was released in July 1966) before the January 1966 session. It would be interesting to compare with your source.

I do hope this is of interest. And thanks for the interesting blog.

Thankyou for your extra research John, that is indeed of a lot of interest, I hadn't heard that before. I think both bands probably took it from the Pete Seeger arrangement thinking about it! Can't say I've ever heard his version though, have you? I think it was a Byrds piece I read on the internet though I can't find it anywhere, so maybe they were wrong. I know it was one of the first songs The Byrds recorded for 5D which would also put it somewhere around January or February 1966 I think. Interesting that two bands should record the same song at pretty much the same independently! Thankyou for taking the time to post and get back to me! 8>)

ReplyDeleteHi again

ReplyDeleteI hadn't heard the Pete Seeger version before yesterday, but I did look for it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Im3oxaQ3Ong

It seems to have the same tune as the Byrds version. For reference, the Misunderstood version is different. Nonetheless it confirms you are right that Pete Seeger inspired both.

That made me curious concerning an original. I can't find that and maybe there isn't an original as such, but I did find this Turkish concert by searching Nazim Hikmet Kız Çocuğu

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BcFDLR-AOWQ

This is a child singing the song. I think it's Nazim Hikmet standing in the background) because lots of other YouTube clips with his name look like the same concert) but obviously I can't be sure.

It follows a different tune again. Assuming it is Nazim Hikmet in the video, then we might infer that this tune is one he approves of.

Wikipedia has some useful information

Thanks again

Thanks for the links John! The Turkish version is very different, it almost sounds happy! I'd never come across an original recording either but I hear there are some, dating back to the 1940s. Interesting to see Hikmet actually in the video, I guess that would be a vote of confidence. I've never heard what he thought of any of the versions of his poem. I would like to think that he would have embraced the hippie movement adapting his song in the name of peace! Thanks for all your research, you discovered more than I had! 8>)

Delete